The Pacific Ocean is a beautiful sight, especially after crossing the Atacama Desert in north-western Chile. A dusty bus journey that can last several days.

Almost immediately, I am surprised by the sheer size of the deserted beach on which I am standing. The blinding white sand sharply contrasts with the deep blue of the ocean. As far as the eye can see, this small sea of sand is in fact five kilometres long for one wide. South of it lies a quiet little town that 15 000 Chileans call home: Chañaral.

The “Pan de Azucar National Park”, which is situated 30 kilometres north of Chañaral, is the natural territory of Humboldt penguins, sea lions, dolphins and otters. Largely renowned in Chile for its exceptional biodiversity, the region seems idyllic. It’s not.

Looks can be deceiving. Chañaral was given front row tickets to one of the most significant sanitary and ecological disaster in Chilean’s history. The reality of the situation is truly dumbfounding.

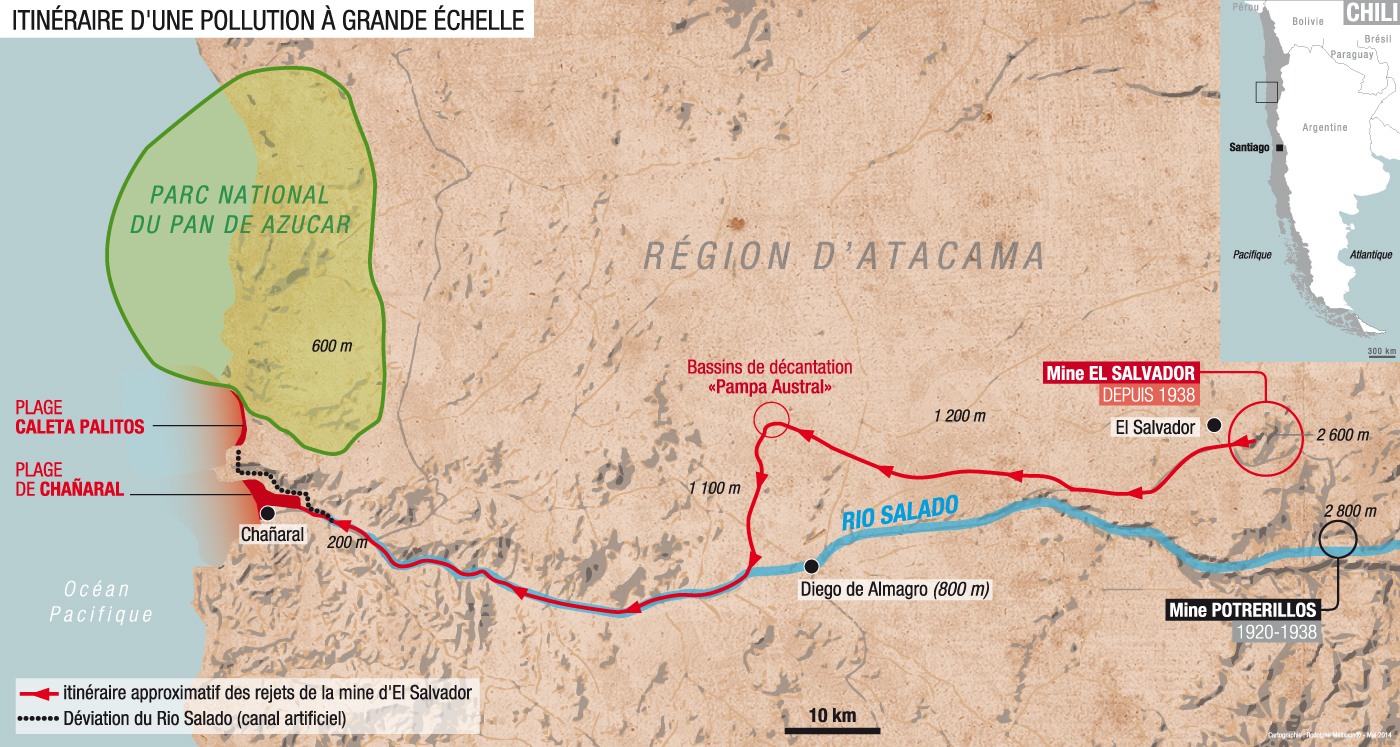

For the past 80 years, the Rio Salado has been inexorably moving dangerous particles downstream. These toxic wastes find their origin 150 kilometres upstream, in the mountains in the east, where copper is intensely mined. So much waste is transported towards the ocean, that entire beaches are literally created in a matter of decades. When the wind blows, the dangerous particles start spreading in the air that the people of Chañaral breathe all day long. The town is slowly and silently dying, poisoned by the copper industry.

“It all started in the 30’s, when the American company Andes Copper Mining started exploiting the huge deposit found in Potrerillos,” explains Alfonso Sepulveda Perez, known as “Poncho”. This cheerful and kind man has been working the National Park for the past 17 years.

The copper extracted from the Chilean mountains counts for 38% of the world’s production, making it the country’s first economical resource. The process that is used to extract copper requires complex physical and chemical treatments, and a layer of rock is considered rich if it constituted of 1.8% of the precious metal or more. The toxic sludge resulting from the extraction process contains high levels of copper, zinc, lead, mercury, molybdenum… that is more than 21 contaminants, mostly heavy metals, with concentrations reaching levels considered 20 to 50 times what the human body can tolerate.

“In 1938, the retention ponds used to capture the contaminated mud from the Porterillos mine started overflowing, recalls Poncho. The Andes Copper used the Rio Salado to siphon away the mine’s waste into the Pacific Ocean…”

This is how, from 1938 to 1989, 350 million tons of sediment (which is the equivalent of a semi-trailer filled of sediment being emptied every single day) were carried by the river towards the bay of Chañaral. Ultimately, these sediments built up into what is today the gigantic toxic beach on which I am standing.

“The Andes Copper’s decision was openly violating a law from 1916, that stipulates the illegality of contaminating water sources with industrial waste“, writes Anglea Vergara, a doctor in history at the Chilean University of Los Angeles.

People from Chañaral started noticing the scarcity of seafood and fish as early as the 40’s, and part of the population who went swimming in the ocean began complaining about the increase in skin deceases. Although the situation was brought to attention at a national level, it isn’t before the 60’s that scientific studies were undertaken… for economic reasons! Indeed, the growing concern for Andes Copper’s management was over the silting of the Bay of Chañaral, where their export harbour was located. They were concerned that the build-up of the sand may impede the smooth functioning that resulted in millions of tons of the copper being shipped around the world.

“When Chile nationalised Andes Copper and changed its name to Codelco in 1971, nothing was done to reverse the water treatment problem in the Chañaral region”, explains Poncho.

The contamination levels kept building up, and in an effort to move the issue further away instead of fixing it, the Rio Salado was diverted in 1975. The waters, still seriously polluted, started pouring their heavy metals in the “Caleta Palitos” creek, only 10 kilomtres north of Chañaral. “The people who come to visit the region are delighted by how white the beach is here. The tourists love it, but they don’t realise that it is not only an artificial beach but a dangerously toxic one!” exclaims Pancho.

In 1983, the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) declares Chañaral as one of the most contaminated towns in the world.

It took another five years, but finally the pressure coming from the international community and the engagement of the local population proved to be a successful combination. The Chilean Supreme Court ordered the company to immediately put a stop to the pollution of the water, and to start decontaminating the area. Such a decision was a first in the nation’s history, and instantly become symbolic for the communities that were fighting industrial development.

Several processes are then set in motion: Codelco finances the construction of a concrete canal leading the wastes from the mine to a brand new tailing pond situated 18 kilometres north of the town of Diego de Almagro. According to the company in charge, the polluted sediments are separated from the water which is then released in the Rio Salado. Furthermore, a number of shrubs and bushes are planted in the vicinity of the contaminated sand dunes with the cooperation of the organisation in charge of the national park. The aim is to trap the toxic dust when blown away by the wind, and therefore limit its dispersion. In total, less than two hectares of shrubs are planted, while the Chañaral toxic sand patch stretches over 500 hectares…

In comparison to the extent of the problem, these actions can be considered purely cosmetic. With a total cost of decontamination that can reach up to an estimated 500 million dollars today, this situation is bound to fester. Neither the government nor the company are ready to make these kinds of investments.

In an effort to reassure the community in December 2003, the president of Chile at the time, Ricardo Lagos, went for a swim in the bay of Chañaral. This staged performance to prove that the water was clean and safe was in fact marketed so that Codelco could get an environmental certification.

But the pressure on the sanitary consequences reached a critical point for the authorities. A health study of Atacama (Servicio de Salud de Atacama) proved that in the years between 1990 and 2007, the main causes of mortality in Chañaral were linked to tumours (24%), circulatory deceases (21%) and respiratory problems (13%).

To compare these numbers with a country we can relate to, in France the mortality rate linked to tumours is of 2.4 for 1 000 inhabitants (source : CepiDC). In Chañaral, it is of 128.3 for 1 000 inhabitants!

Although these figures may seem significant, no study has yet linked the environment scandal in Chañaral to the health problems of its local community. However, Doctor Sandra Cortés explains that “international publications clearly demonstrate the direct health consequences related to heavy metal expositions.”

While leading me into his office and carefully closing the door, Manuel Alejandro Aguillera of the local Tourism Office seems to have lost all hope: “The authorities have abandoned us, and Codelco blames its US predecessor Andes Copper Company. We are utterly helpless!”

Manuel’s feeling is understandable. In 2009, Michelle Bachelet who is the running president of Chile at the time, is challenged by a group of deputies who publish a report asking for the evaluation of the risks and the consequences for the wellbeing of the Chañaral community. The health minister is asked to intervene immediately in order to protect the most vulnerable, the young and the elderly. To this day, no measures were taken to follow up with this report.

Is the desertion of their hometown the only solution left to the inhabitants of Chañaral, as it was the case for the people of Potrerillos? Located right next to the Rio Salado, this little town was declared “saturated by sulfur dioxide and particulate material” by the government. The entire population, mostly constituted of miners and their family, was displaced to El Salvador, 25 kilometres away.

Travelling along the bay, I am back on the road built where the ocean once was. Caleta Palitos is situated less than 10 kilometres north, where a second toxic beach can be found.

The northern section of this area is part of the national park, where 25 000 tourists come to visit every year. The question is to know if one of the most important natural reserves of the country is being affected by the pollution. Without a doubt, the answer is yes.

In 2011, a veterinary student dissected a sea lion only to find that its bones were blue. Copper is incriminated once and again. “Pan de Azucar’s wildlife isn’t spared, explains Poncho. Dead birds are regularly found. Some species are able to adapt, such as a type of algae that is named “lama”. Several studies have been conducted by interns, but we were never given the results…”

During the 1988 trial, the Chañaral community heavily criticised the complete silence coming from the CONAF (the management of the national park) while the contamination of the marine fauna and flora of the reserve was clearly visible. To this day, it is impossible to find a single achieved study on the consequences of the presence of toxic waste in the protected zones of the national park.

“The authorities keep telling that the mine of El Salvador is an opportunity for wealth, but for us, it only brings poverty. Before, Chañaral was a small fishing town with a bright future. Fish and seafood could be found in abundance. Today, they left us with a completely sterile marine environment.”

By poisoning their air and water, the industry is slowly killing an entire Chilean region, silencing its population along the way.

It is known that silence is golden. In this part of the world, silence is made of copper.