Where does the Camaret coral go?

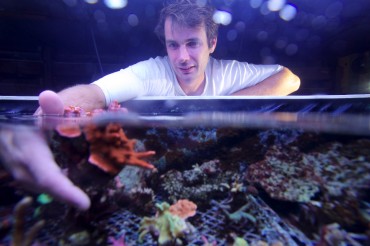

While the Camaret coral farm contributes to the environmental security of wild coral reefs, it also makes Remi and Johan a good living.

The vast majority of the coral farmed at Camaret goes to aquarium outlets, between 10 and 15% is sold to individuals and a small amount goes towards research by large cosmetic companies that are investigating the beneficial properties of coral and may use it in protective creams.

The vast majority of the coral farmed at Camaret goes to aquarium outlets, between 10 and 15% is sold to individuals and a small amount goes towards research by large cosmetic companies that are investigating the beneficial properties of coral and may use it in protective creams.

Trade and transport of wild and farmed coral is tightly controlled and regulated by the Washington Convention. All traded and transported coral is identified by a Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora number (also known as a CITES number), which is a passport required for import and export.

Transportation presents a number of challenges; coral must be delivered in under 36 hours, it is incredibly sensitive and must be maintained at an average temperature of 25 degrees centigrade.

Transportation presents a number of challenges; coral must be delivered in under 36 hours, it is incredibly sensitive and must be maintained at an average temperature of 25 degrees centigrade.

The coral branches travel submerged, upside down and attached to a piece of polystyrene in something similar to a bag you would buy a goldfish in. It is vital that the branches don’t touch the sides of the bag and damage the polyps.

The travel bags are then installed inside a polystyrene tank that is cooled in the hot summer months and heated during the winter.

Back at the farm, Johan stepped away for a moment to deal with a customer from Quimper who owns a pet shop and had come to collect his order of coral. After much handshaking and chatting – mostly about coral in Latin – they got down to business. One branch of coral costs between 10 and 35 Euros.

Back at the farm, Johan stepped away for a moment to deal with a customer from Quimper who owns a pet shop and had come to collect his order of coral. After much handshaking and chatting – mostly about coral in Latin – they got down to business. One branch of coral costs between 10 and 35 Euros.

While they were doing business, we moved away and in the corner of the room, spotted a tank set aside from the rest, inside were giant clams, Tridacna gigas, the largest living bivalve mollusc in the world and one of the most endangered clam species. These giants can grow up to 1.3 metres long and weigh up to 200 kilograms. They are threatened by overfishing and farming them is an interesting alternative that might secure their survival.

Giant clams require similar conditions as coral to grow; they need 20 degree centigrade water and also subsist from a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae.

Giant clams require similar conditions as coral to grow; they need 20 degree centigrade water and also subsist from a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae.

Remi and Johan are attempting with French state research organization (CNRS) to rear Giant Clams from their breeding pair and just a few days before our visit, they collected five million larvae and although only about forty will survive, the two friends are hopeful. “If we are successful, then we will become the first farm in Europe to breed Giant Clams in tanks!” said a cautiously hopeful Johan.

They are doing something special in Camaret behind their blue door, but they have a long path ahead.