Sharks, the architects of our world

A sorry record has been broken in 2015. According to the International Shark Attack File, there were 98 “unprovoked” shark attacks on humans last year. Six of which were fatal. Australia counts for one death, Hawaii another one, and Egypt one as well. The three remaining all took place on French territory.

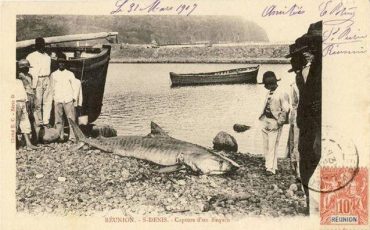

Réunion Island, a small volcanic rock in the Indian Ocean, saw a 40-kilometer-long stretch of its west coast hit twice by fatal shark attacks in 2015. One third of the worldwide statistic. These tragedies happened on some of the most popular beaches of the island, after four years of public communication on the risks, after a law was passed to forbid all marine activities on the open beaches, after the number of local surfers reached an all-time low and most of the island’s surf schools closed. The coastal economy faced one of its most crippling struggle, some say worse than the chikungunya crisis of 2006.

The situation was particularly paradoxical for the diving centers. On one side, tourists stopped asking for discovery dives in the waters of Réunion Island, supposedly swarming with man-eating predators. On the other, experienced divers seeking a rush are left unsatisfied: sharks are hardly ever seen by scuba divers. To expose this absurdity, the diving centers offered a temporary action: “If you see a shark, you dive for free”. Never did a single client get his money back.

The situation was particularly paradoxical for the diving centers. On one side, tourists stopped asking for discovery dives in the waters of Réunion Island, supposedly swarming with man-eating predators. On the other, experienced divers seeking a rush are left unsatisfied: sharks are hardly ever seen by scuba divers. To expose this absurdity, the diving centers offered a temporary action: “If you see a shark, you dive for free”. Never did a single client get his money back.

With so many contradictions, and to separate facts from rumors, the public authorities turned to science. Although something unexpected happened: “We couldn’t answer all the questions people were asking, because prior to 2011, there simply wasn’t a single scientific study on sharks ,” says Marc Soria, researcher at the IRD, the French Institute for Research and Development. The doctor in behavioral ecology invited me for a chat in his air-conditioned office at the university of Saint-Denis. He offered me an excellent cup of coffee, and an explanation on the situation: “Before the tragic episode of attacks started, nobody took any interest in sharks. We would hear about the tiger shark here and there, because it’s an animal that may take a bite out of fishermen’s catches. The predator was considered a nuisance, and nothing more.”

Indeed, sharks have always carried a nasty reputation that is easily verified: In 1956, the Palme d’Or at Cannes was given to the ground-breaking documentary “The Silent World” by Jacques-Yves Cousteau. On the screen, the propeller of the legendary Calypso hits a young whale. The poor animal is too badly injured, and put out of its misery with a rifle shot to the head. Then, when the first fins break the surface, attracted by the carcasse, the narrator wonders: “Where do all these sharks come from? We are far away from the closest shore, and there are 5000 meters of water beneath our hull. For us divers, sharks are the deadly enemy. We have often encountered them, but never have we seen so many at the same time.” Later in the film, which was also awarded an Oscar for best documentary in 1957, strong graphic scenes of shark killing take place on the deck of the boat. “All around the world, says the narrator, sailors despise sharks. The divers are unstoppable. Nothing can go against such an ancestral hate. Every crew member looks for a weapon, anything to hit, catch, lift.”

Indeed, sharks have always carried a nasty reputation that is easily verified: In 1956, the Palme d’Or at Cannes was given to the ground-breaking documentary “The Silent World” by Jacques-Yves Cousteau. On the screen, the propeller of the legendary Calypso hits a young whale. The poor animal is too badly injured, and put out of its misery with a rifle shot to the head. Then, when the first fins break the surface, attracted by the carcasse, the narrator wonders: “Where do all these sharks come from? We are far away from the closest shore, and there are 5000 meters of water beneath our hull. For us divers, sharks are the deadly enemy. We have often encountered them, but never have we seen so many at the same time.” Later in the film, which was also awarded an Oscar for best documentary in 1957, strong graphic scenes of shark killing take place on the deck of the boat. “All around the world, says the narrator, sailors despise sharks. The divers are unstoppable. Nothing can go against such an ancestral hate. Every crew member looks for a weapon, anything to hit, catch, lift.”

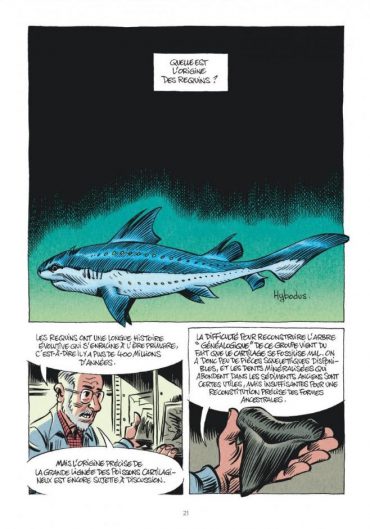

Bernard Seret is a shark specialist at the Natural History Museum in Paris. In the 1980s, he was sent by the IRD to West Africa for the study of rays. Back then, he witnessed “phenomenal quantities of sharks on the port’s landing sites, between Mauritania and Angola. It was curious that nobody took any interest in them. I sort of fell down the rabbit hole.” Along his studies and publications, the shark expert realized how fascinating their history was. “With our recent methods to study phylogenetic trees, he explains, we can retrace the group of cartilaginous fish, which comprises sharks, rays and chimaeras, back to the Devonian. It’s the earliest of geologic eras.” More than 450-million-years-old, it is also known as “The Age of the Fish”, when marine animals ruled the world, long before the dinosaurs. “Unfortunately, says the French biologist, their cartilaginous skeleton doesn’t fossilize very well. We are missing bits and pieces. Still, we are confident that sharks as we now know them appeared some 150 to 250 million years ago. Which means they survived the famous five mass extinctions.”

Sharks have occupied the top of the food chain for such a long time that they have been poetically nicknamed the “architects of our world”, such as in the award-winning documentary “Sharkwater” by Rob Stewart. As a top predator, their constant pressure on the weakest specimens forced marine species to evolve. This may be why fish now swim in large schools to avoid being singled out, and it may also explain the origin of complex camouflage strategies. Who knows, sharks are maybe responsible for the very first organism to try its luck on dry ground, fed up with the constant risk of being eaten?

Their biology is as interesting as their history: “Sharks have a sixth and seventh sense, explains Bernard Seret. Just like most other fishes, the top predators have what we call a lateral line. It allows them to feel what is happening on their sides. More interestingly, sharks are equipped with a complex network of ampullae of Lorenzini. These little organs are disseminated on the ventral face of the animals, around their head, and can pick up the faintest electrical field that every living creature emits. Preys that hide in murky waters or in the sand can still be targeted.” All of these various characteristics are fairly easy to study. Scientists only need to get a shark out of the water and dissect it. However, and until recently, most of marine animals were difficult to examine in their natural habitat, which kept a mystery around their behavior and whereabouts.

Their biology is as interesting as their history: “Sharks have a sixth and seventh sense, explains Bernard Seret. Just like most other fishes, the top predators have what we call a lateral line. It allows them to feel what is happening on their sides. More interestingly, sharks are equipped with a complex network of ampullae of Lorenzini. These little organs are disseminated on the ventral face of the animals, around their head, and can pick up the faintest electrical field that every living creature emits. Preys that hide in murky waters or in the sand can still be targeted.” All of these various characteristics are fairly easy to study. Scientists only need to get a shark out of the water and dissect it. However, and until recently, most of marine animals were difficult to examine in their natural habitat, which kept a mystery around their behavior and whereabouts.

The shark expert from the Natural History Museum in Paris explains how an exciting shift is currently taking place: “Today, there is a boom in the study of sharks’ behavior. The revolution was made possible by the new generation of beacons, these tiny technological wonders that can capture all kinds of data. The scientific community is taking huge steps in understanding how the predators move around.” A great white shark named Nicole was tagged in South Africa in 2003. After retrieving the recording beacon, scientists were baffled to discover that the animal crossed the Indian Ocean all the way to Australia. On the way, Nicole dove several times to an unbelievable depth of 1000 meters. “When we looked at where Nicole decided to dive, says Bernard Seret, we realized it was all but randomly. The great white shark aimed for underwater topographic places where the earth’s magnetic field tightens. Our hypothesis is that the shark’s ampullae of Lorenzini are able to detect the animal’s location on the planet depending on the variation of the magnetic field. Why else would they swim down to such astounding depths? You don’t need to go that deep to find some seriously cold water and get rid of parasites.”

With such incredible feats, no wonder sharks have become the lords of the oceans. Slowly we realize the essential role they play in the marine ecosystems. For the past decade or so, they are being considered the centerpiece of the oceans, a responsibility confirmed by the 2007 study “Cascading Effects of the Loss of Apex Predatory Sharks from a Coastal Ocean”, published in the magazine Science. Scientists from the East Coast of the United States demonstrated how the near extinction of the Atlantic great sharks annihilated a century-old scallop fishery. It’s called “indirect cascading ecosystem effects”. Bernard Seret explains why it shouldn’t be considered as good news: “Species that are at the top of the food chain, such as pelagic sharks, play a regulatory role. They are the custodians of a fine balance between predators and preys. If you eliminate entire groups of apex predators, more or less catastrophic cascading effects are observed. In most cases, the consequences are far from being beneficial to humans.”

Completely oblivious to this, mankind is supposedly emptying the planet’s oceans of its sharks, often as bycatch in the fish industry, but mainly to supply the humongous Asian market who is very keen on shark fin soup. A delicacy served during many weddings as a sign of good fortune. The term “finning” has been used to describe the barbaric and inhumane practice of slicing off the shark’s fins and then throwing the animal back in the water, still alive and unable to swim. It is very hard to measure the impacts of finning, for the simple reason that it often takes places in the open ocean, far away from prying eyes. A 2006 study often used as a reference calculated that between 26 and 73 million sharks are being fished every year. Many people round up the amount to 100 million of sharks killed every single year by mankind, a large-scale carnage synonym of time bomb. Today, no one can know for sure what the oceans will look like in a future devoid of sharks.

Completely oblivious to this, mankind is supposedly emptying the planet’s oceans of its sharks, often as bycatch in the fish industry, but mainly to supply the humongous Asian market who is very keen on shark fin soup. A delicacy served during many weddings as a sign of good fortune. The term “finning” has been used to describe the barbaric and inhumane practice of slicing off the shark’s fins and then throwing the animal back in the water, still alive and unable to swim. It is very hard to measure the impacts of finning, for the simple reason that it often takes places in the open ocean, far away from prying eyes. A 2006 study often used as a reference calculated that between 26 and 73 million sharks are being fished every year. Many people round up the amount to 100 million of sharks killed every single year by mankind, a large-scale carnage synonym of time bomb. Today, no one can know for sure what the oceans will look like in a future devoid of sharks.

With such astounding revelations, the predator slowly lost its status of mindless killing machine to make its way up to the highest rank in ocean conservancy. A incredible U-turn, made possible with the help of many popular documentaries. Countless nature protection associations launched their own shark-conservancy programs to protect and raise awareness. Today, very few people are oblivious to the fact that the Great White Shark is on the “IUCN red list of endangered species” and is protected in most of the waters it visits.

By the way, a specimen of Great White Shark was caught in Réunion Island in October 2015, an unprecedented event in living memory. The 2.9-meter-long juvenile was feeble and covered in parasites. The fishermen failed to identify it, and proceeded to take it out of the water and back to port. It was a mistake, since the Great White is not a targeted species in Réunion Island. The two species that have been threatening marine activities are the tiger shark and the bull shark.

The tiger shark is relatively well studied because it is easy to attract and catch. We know that it is a pelagic predator, meaning it lives most of its life in the open ocean. But that doesn’t prevent some specimens to visit the coast. As a matter of fact, it is a 3.5-meter-long tiger shark that killed Talon Bishop in Étang-Salé, on the west coast of Réunion Island, on February the 14th, 2015. The unfortunate young girl was peacefully swimming in waist-deep water.

The tiger shark is relatively well studied because it is easy to attract and catch. We know that it is a pelagic predator, meaning it lives most of its life in the open ocean. But that doesn’t prevent some specimens to visit the coast. As a matter of fact, it is a 3.5-meter-long tiger shark that killed Talon Bishop in Étang-Salé, on the west coast of Réunion Island, on February the 14th, 2015. The unfortunate young girl was peacefully swimming in waist-deep water.

Still, the vast majority of shark related accident since 2011 in Réunion Island implicated a very specific species: the bull shark, one of the least studied sharks in the world. “It’s a species rather difficult to observe, confirms Bernard Seret. It often lives in waters were the levels of salinity are low, such as in estuaries, close to river mouths or even up some large rivers. These zones are typically not popular for aquatic tourism.” The formidable predator is also known as the Zambezi Shark, since it is capable of swimming upstream and even living its whole life in the fresh waters of large rivers such as the Zambezi in Mozambique. Some specimens were even caught in Brazil, up the Amazon some 3’700 kilometers from the closest shore.

“It is a large shark that can reach up to 4-meters-long, says Bernard Seret, and weigh up to 300 kilos. It occupies all of the tropical and subtropical zone. It is a coastal shark, yet an individual might migrate across an ocean as it was once observed with a female bull shark that was tagged in the Seychelles, swam all the way to Madagascar to give birth, and then swam back to the Seychelles. Today, we have some information on this species, but no one is able to say how many individuals visit the coast and beaches of Réunion Island.”

An elusive and remarkable fish that deserves all of our attention. If we manage to find it.