A disturbing testimony

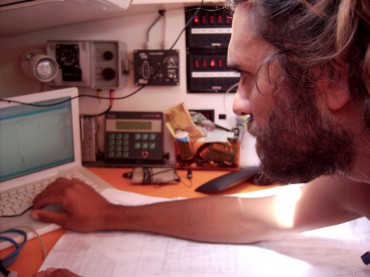

July 2008: Chloé and Florent Lemaçon left Brittany with their three-year-old son, Colin, on board their 12.5 metre Ferro-cement yacht, Tanit.

They crossed the Mediterranean, travelled along the Suez Canal, across the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, heading for Kenya. Mid-March 2009, following the recommendations of the armed forces, they changed course and headed for the Seychelles. On Saturday 4 April 2009, 950 kilometres off the coast of Somalia, they were attacked and taken hostage by five pirates. The following day relatives alerted the Admiral of the French naval forces in the Indian Ocean (ALINDIEN), that they had not had news from the boat for 24 hours. On Tuesday 7 April in the evening, the frigates from the Atalante mission located the sailing vessel and waited 24 hours to make contact with the pirates. The assault was ordered on 10 April. Florent Lemaçon and two pirates died during the attack. The three surviving pirates were sent to France for trial.

It took a book on Chloé Lemaçon’s version of events for the French state to acknowledge the facts behind the bullet that killed her husband. During the trial from 14-18 October 2013 held in Rennes, the cloak of secrecy was kept firmly in place. Today however, Chloé Lemaçon has granted us an exclusive interview and insights on the tragic consequences of a hazardous military operation that took the life of her husband.

###

OCEAN 71 Magazine – Why did you and Florent choose to cross the Gulf of Aden despite the risk of piracy?

CHLOÉ LEMAÇON – Tanit is a heavy displacement boat that does not go upwind well, so cruising the west coast of Africa would have been too long and too difficult and probably no safer in terms of pirate encounters. It is important to understand that piracy has always existed and will always exist, and not solely off the coast of Somalia. It is common knowledge amongst sailors like us that wherever you are in the world, piracy is a risk, and sometimes a greater one than where we were – for example, we had met cruising sailors in the Caribbean that had been brutally attacked in Venezuela. In those parts, the pirates are hooked on crack, are out of control and don’t think twice about executing the sailors once they have robbed them. They can descend upon your boat at anytime, anywhere and there is no warning or protection.

So encountering Somali pirates was a potential risk?

Yes, but at the time that we left, their modus operandi was well known. They were only taking cargo ships with a commercial value and were not mistreating or executing their hostages. Florent researched and read everything he could find on the subject, he knew the issue inside out. We felt prepared and approached the matter with our eyes wide open.

In Ismailia in Egypt, you met Jean-Yves Delanne, skipper of the sailing yacht Carré d’As IV, which had been captured by pirates seven months earlier. What did he tell you?

He told us that he sailed between the island of Socotra and the coast of Somalia, straight through the risk zone, far from the safety corridor. Jean-Yves didn’t take any of the precautions that we were planning. Statistically, the chances of us being taken were very low, particularly as we had met several yachts and chartered multihulls that hadn’t had any issues in the area.

When the pirates captured you, Hervé Morin, the French Minister of Defence at the time, suggested you were irresponsible. And yet you were knowledgeable sailors?

Morin fuelled the media appetite for a story that sells by calling us uninformed “sea tramps” who were endangering the life of our son, and so instead of explaining that attacks on cruising boats of little to no value were so far unprecedented and that most piracy up until our experience had been centred on commercial shipping, they concentrated on this. The pirates were interested in the ransoms that merchant ships and trawlers’ insurance companies would pay. At the time, the government was not forbidding entry to the area, they were issuing recommendations, all of which we complied with.

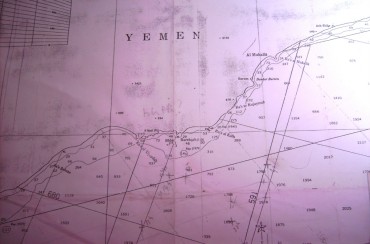

Contrary to what the state suggested, you were not in the risk zone?

At the time the pirates boarded our boat, we were exactly 512 nautical miles (948 kms) off the Somali coast. We were following the instructions given to us by the commander of the frigate Le Floréal to the letter, not once did he tell us to turn around. Each day we reported our position via satellite phone to the Admiral in charge of French naval forces in the Indian Ocean (ALINDIEN). Up until that moment on Friday 3 April, there had never been an attack so far away from the coast of Somalia. But unbeknownst to us, just a few miles from our position, five pirates had missed their attack on a cargo ship called Africa Star…

And no one warned you of this attack?

Incredibly no. If we had been warned we would have been on alert and would have immediately changed course.

Media coverage of your hijack was very high, what were the repercussions for you?

When the Ponant and the Carré d’As IV were seized, the French government decided to send a strong message to the Somali pirates. By encouraging the media to communicate on Tanit and our situation, the government endangered us – partly because the pirate commander could measure the level of interest in the case on the Internet and partly because it precipitated the assault.

Do you mean you did not want to be rescued?

Long before we were attacked, I knew that our best chance of survival would be to let the pirates take us ashore and to negotiate a ransom. The magazine covers depicting me in tears imploring someone out of shot were deliberately misleading. I was not begging the military to free us, but to leave us! Back in France the ministry of Foreign Affairs told me that it wasn’t up to me or my family to decide whether we wanted to be rescued or not, France is a sovereign state that rescues its citizens without consulting them. In most cases these rescues are successful…

Did your family have the means to pay a ransom?

It would not have been easy, but they could have gathered the amount of money needed to free us. But no one at the time asked them if it might be possible.

Do you think the French military would have intervened in any case?

It is not for me to say. The operations commander on site, Captain Paul-Henri Desgrées du Loû, confirmed receiving very clear orders to prevent our sailing boat being taken to Somalia. Hervé Morin maintains that the decision to intervene was made by the president of the Republic, Nicolas Sarkozy, after a restricted council session.

Did their evidence on the stand give you a better understanding of how the rescue went wrong?

Contrary to what they have said up until now, I am certain that the commandos did not wait for three pirates to be on deck before shooting. The official objective was to save us. So be it. But what I don’t understand is why they launched the assault without seeing any pirate on deck? The army must have considered the possibility that we would all be shot.

Do you mean that the rescue attempt was rushed?

Not only rushed… The day before the assault, on Thursday, the military said they used a sniper to take down our mainsail and slow the boat down. There were 28 bullet holes in the mast! You can imagine the level of tension onboard our boat. Later that same evening, two of the pirates put their weapons down on the deck, they wanted to turn themselves in. When no one came to arrest them, they simply took up their weapons again.

And the following day the assault is launched…

Everything happened very quickly. We were holed up in our cabin. We could hear machine gun fire from every direction; a bullet narrowly missed Colin. The pirates panicked. It was easy, given the context, to try to make us believe that Florent fell victim to a stray bullet.

Is that what the military told you once they had you aboard the frigate Aconit?

They did not ‘say’ that, but the captain insinuated that it was absurd to imagine any other scenario. It was only when Dorian, Steven – my fellow crewmembers – and I were talking it all through and sharing our different points of view on what happened that we realised that something was wrong.

What do you mean?

I had the feeling that they wanted to use my state of shock to confuse me. As soon as we landed in Djibouti, the military prescribed Stilnox, but I hid the pills in my pocket. When we got to Villacoublay, they wanted to give me more medication and there was even talk of institutionalising me, but my father in law and best friend, a psychiatrist herself, opposed them.

Back on French soil, did the French presidency office contact you?

Several times, yes. I felt harassed. I finally agreed to meet on the condition that it was face to face with Nicolas Sarkozy, but this was not granted, as the President never meets anyone alone. The chief of staff, Edouard Guillaud, was present for the meeting. Nicolas Sarkozy told me that he was responsible for the death of Florent as it was him that ordered the assault. He asked me what he could do for me, saying «It is my duty to aid the widow of a French citizen. With money, the sadness is easier to overcome.» I said that he would never have asked me to meet him if a pirate had truly shot my husband. He replied: «I am not proposing money to buy your truth…your truth belongs to you. You can tell what you want to whomever you wish…»

What do you think he was expecting of you?

That I tell the media that the bullet that killed Florent was French. At the time I was missing elements. I was in mourning and would not have been taken seriously. Imagine what would have been said if I had been put in a psychiatric hospital.

If you had accepted the money proposed to you by the state right away, do you think you would have had the same freedom of speech?

I didn’t want to talk about money as long as the state was refusing to acknowledge the facts. And in any case, regardless of presidential promises, Sarkozy couldn’t just unlock funds in a snap of his fingers. At a second meeting, the Minister of Interior at the time, Claude Guéant, told me about a secret pension fund for war widows and assured me that they would pay 1,000 Euros monthly. After that I received a call from an embarrassed administrator responsible for the compensation payments, telling me that the fund no longer existed. On leaving the presidency office, Guéant had the nerve to tell me that my son would be a ward of the nation and would have access to the best military schools… «We’ll make a good little soldier of him,» he said.

Knowing that the investigation was about charging the pirates and not about clarifying the circumstances surrounding the death of your husband, you decided to publish your story in a book called “The Journey of Tanit”. What happened when it was released in May 2010?

Just after my interview on Élise Lucet’s news programme (France 2 television channel), the AFP put out the story «Morin has spoken. The bullet is French.» But the only thing that the French journalists were interested in was whether or not I was going to take the money!

Vice-admiral Marin Gillier, commander of the Naval Special Forces at the time, admitted at trial that «there had been a misunderstanding by a French combatant» – what did you feel at that moment?

The ballistics expert confirmed the bullet was French – the military knew that fact immediately after the operation and removed the bullet. Had they told the truth from the beginning we could have avoided four and a half years of proceedings.

What evidence did investigators find onboard Tanit?

Our boat spent three weeks in the hands of the military before the investigators could gain access. Gilles Lacroute, who led the investigation, saw the boat in Djibouti and again when it was delivered from Toulon to Brittany. He confirmed that there was no trace of bullet holes in the deck, and yet the commandos stated that they had responded to sustained fire from the pirates inside the boat.

What were your expectations regarding the trial of the pirates in France?

My crewmates, family and I brought a civil action in order to gain access to records and to be able to monitor the proceedings, but we were denied crucial evidence such as the reconstruction of the assault and the transcripts of the satellite telephone conversations between the army and the pirates.

Are there other points that you feel still need to be clarified?

Absolutely. For starters, why did Desgrées du Loû, the commander of operations, resign shortly after the fact? No one asked him this question during the trial. And no one asked Gillier or Morin if it was normal practice that one of the pirates was executed on board. But this wasn’t about the army, this was a trial brought by the state against the pirates.

During the trial in France, how did you feel coming face to face with the Somali pirates that held you hostage?

Of course it was very strange to see them. I couldn’t take my eyes off them. They looked lost in the ornate room crowded with gilt moulding and gold. The place was packed with journalists. On the first day of the trial they described their day-to-day life. They told the court how the 2004 tsunami and the 2005 drought made them destitute: wrecked boats, depleted fish stocks, and decimated livestock. Mohamed Mahamoud and Abdelkader Ousmane Ali, both fishermen, could no longer feed their families. Neither could Mahamoud Abdi Mohamed, a nomad whose father was shot when he was just eight years old.

They were on trial for ‘the hijack of a vessel by force or threat, arrest, kidnapping, false imprisonment or arbitrary detention of several people, by an organised gang’. How did simple fisherman get to this point?

In 2009, famine forced them to seek employment in the town. A pirate commander recruited them, provided them with cloths, khat – the local drug – and a hundred dollars in exchange for ‘doing a job’. The nature of the job was not divulged. Only Mahamoud Abdi Mohamed knew and it was too late for the others to back out. The group was put in a boat and sent out to sea armed with Kalashnikovs and just enough water and fuel to reach the target ship: Africa Star. They tried to seize her and failed.

Do you know why they failed to seize the ship?

Their ladder was too short ! A twist of fate. We talk of organised gangs of pirates, but this absurd detail demonstrates exactly how disorganised they actually are. They were destined to perish in the Indian Ocean, almost a 1,000 kilometres from Somalia – that is until they spotted our boat right under their noses. They say it themselves ; we saved their lives.

According to the pirates’ lawyer, the three defendants are small fry. Why is it that the pirate ringleaders are never brought to justice?

It is a matter of political will. During the trial, the judiciary police from Brussels who were investigating the 2009 hostage crisis involving the Belgian boat Pompei, managed to trap the Somali pirate commander, Afweyne, by enticing him to Belgium where they arrested him. For four and a half years I have been told that it is too complicated to get our hands on the man that ordered the pirates to take Tanit when we know that it is the khat seller in a town of 400 inhabitants, the only person to own a 4×4 and a stone house. What interests the French state is selling weapons and military dominance of the region; they aren’t going to bother with Somali pirate chiefs.

At the end of the trial you spent 30 minutes alone with the pirates who had been convicted to nine years in prison. What did you talk about?

They learnt French in prison so it was quite moving to be able to communicate in the same language. They told me that they think of Florent constantly, they asked for my forgiveness, and explained that they had tried to oppose their chief. Abdi even removed the bullets from his weapon without telling anyone. They too were frightened throughout the week that ended so tragically. I explained that it wasn’t worth them trying to appeal and encouraged them to continue on the right track by studying and working.

What relations do you have with them today?

Everyone makes mistakes. They are paying for theirs. Now, we must all look to the future. It’s a bit like a pact amongst us all. To get through this, they are going to need support. I sent them Somali-French dictionaries, a novel by Monfreid and a guide to the rights of prisoners. I also managed to inform Abdi’s family, who hadn’t had news of him for four and a half years, that he is alive and imprisoned in France.

No one had told them earlier?

No – it’s a sad but real fact.

What are you doing at the moment?

My son and I used the compensation payments paid to us by the French government (50 000 Euros for the lawyer fee and 300 000 Euros), to move to Madagascar and complete the project of building a school and eco-lodge that Florent and I were planning to do together.

###

Interview by Marie Dufay