The Abbot Point’s battle

“Try to picture 150 000 trucks lined up bumper to bumper, over two thousand kilometres”, explains Richard Leck, the Australian WWF campaign director of “Fight for the Reef”. “Now, fill these trucks to their maximum capacity and you get three million cubic meters. This is the amount of dredging material that the Great Barrier Reef’s governing body has agreed at the end of January 2014 to dump in the World Heritage Area”.

What is peculiar in this situation is that the governing body Leck is talking about is the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), established in Queensland, Australia, in order to protect the reef. It was founded in 1975. Lately, its board has been under a lot of pressure because the reef is seriously threatened.

To fully understand the current situation, we need to go back in time, in June 2013 more precisely. The political environment of Australia was in turmoil, following the resignation of Julia Gillard, Prime Minister in office since 2010. National elections were held, and Tony Abbott, leader of the Liberal Party was elected. He is now running the country for the next 3 years. Already in only six months the new Australian government has arguably become the most hostile to its nation’s environment in history.

It starts in December 2013, when the Environment Minister Greg Hunt backtracked on its election promise to send a custom boat into the Southern Ocean during whaling season, to the great despair of the NGO Sea Shepherd. January 2014, the decision was made to slaughter endangered great white sharks in Western Australia, for “beach protection”. Less than a month after, in February, ancient forests of Tasmania – harbouring some of the planet’s tallest trees – are threatened to be removed from the World Heritage possible listing.

But the most shocking and controversial decision was the one made last December. A week before Christmas, Greg Hunt approved a proposal by North Queensland Bulk Ports to massively expand their coal terminal at Abbot Point. What will possibly become the largest coal port in the world is situated only 50 kilometers north of the pristine Whitsunday islands, one of the jewels of the Great Barrier Reef.

Between 2012 and 2013, there were almost 11 000 reported commercial ship movements through the reef. These numbers will more than double if all the proposed expansions of the five key trading ports are approved. A massive increase in risk of accidents is forecasted, right in the middle of the marine park that is roughly the size of Italy.

Between 2012 and 2013, there were almost 11 000 reported commercial ship movements through the reef. These numbers will more than double if all the proposed expansions of the five key trading ports are approved. A massive increase in risk of accidents is forecasted, right in the middle of the marine park that is roughly the size of Italy.

For five years a group of Australian and Indian mining corporations have set their sights on the Galilee Basin. This geological basin in the western part of Queensland is predicted to become a coal El Dorado, with promises to boost Australia’s economy and employment. This is exactly what Tony Abbot wishes for his country, at any cost. What the government isn’t saying is that more than three quarters of all the profits made by these mining companies will be going to the foreign owners of the mines, mostly Indian.

The big problem with the Galilee Basin, as with much of the Australian continent for that matter, is its remoteness. Located 500 kilometers inland, with no towns nearby, it lacks all the basic infrastructures. The mining companies are therefore planning to build an airport, roads, power stations, water infrastructure, and several hundred kilometres of railway to bring the extracted coal all the way to Abbot Point and other export ports so that it can be shipped to India and China, the current largest coal import nations. On the other hand, labour will have to come in from somewhere.

To non-Australians, the concept of “Fly-in, Fly-out”, or “FiFo”, is unfamiliar. It is the lifestyle of people who are required to travel to their jobs by plane, and live for extended periods of time on site. Typically, these employees live and work away from their community for two weeks straight, and then get to come home for a whole week. This is the type of work-force that will be operating in the nine “mega mines” that are planned for the Galilee Basin, five of which would each be larger than any coal mine currently operating in Australia.

Recent studies have proven that “FiFo” lifestyle greatly affects the employees and their community in negative ways. Long shifts’ stress, unhealthy food, drug, alcohol, regular absence from home are few of the concerning factors.

One of the strong opponent to the industrial projects is Queensland’s tourism industry. Most of the 67 000 employees of this 5,4 billion dollars industry live close to their jobs. Furthermore, unlike a temporary mining boom, tourism is a long term industry; as long as the Reef is healthy, that is.

And this is the subject of the recent heated debate. By approving the dumping of these 3 million cubic meters of dredge spoils, the GBRMPA, the agency tasked with protecting the Reef, is scaring the tourism and fishing industries, and disappointing the various NGOs who are fighting against the port’s expansion. Sediment from dredging could suffocate corals and seagrasses and expose them to poisons and high levels of nutrients.

“Dumping your waste in the World Heritage Area is not an acceptable way of doing business, says Richard Leck with great disappointment. The issue here is not so much the development in itself, but how this development is occurring. And it is the first stage of Abbot Point’s expansion that requires these millions of tons of mud to be dredged. There are a whole bunch of other developments along the coastline that are coming up for approval as well, and most of those have a bigger amount of dredging and dumping involved. Our concern is that by approving Abbot Point’s development, it will make it easier to approve the other ones as well”.

What is clear is that failures in past developments have certainly not prevented this recent approval.

Still in Queensland but south of the Great Barrier Reef sits the town of Gladstone, and its notorious harbour. In order to create a shipping channel, the seabed was dredged in 2011 and the millions of tons of mud were then used to create a bund wall, designed to prevent inundation or breaches. For reasons that still need to be identified, harmful material such as acid sulphate soil leaked from the wall into the harbour. Fishermen and environmentalists claim turtles, dolphins, dugongs and crabs have died as a result of the seabed being dredged and dumped.

“How can even more reef dumping be approved, when we’re still investigating the destruction caused last time?” said senator Larissa Waters, Australia’s Greens environment spokeswoman. “We can’t allow the devastation in Gladstone, which tourism and fishing operators are still suffering from, to be repeated anywhere else in the Great Barrier Reef. Deaths of marine animals and outbreaks of fish mutilations followed the creation of the shipping channel in the Gladstone Harbour”.

“How can even more reef dumping be approved, when we’re still investigating the destruction caused last time?” said senator Larissa Waters, Australia’s Greens environment spokeswoman. “We can’t allow the devastation in Gladstone, which tourism and fishing operators are still suffering from, to be repeated anywhere else in the Great Barrier Reef. Deaths of marine animals and outbreaks of fish mutilations followed the creation of the shipping channel in the Gladstone Harbour”.

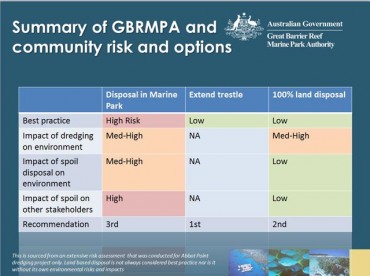

What is troubling is that dredging and dumping are not the only options for the expansion of Abbot Point. An official document from the GBRMPA explicitly favours two other possibilities. One of them would be to dispose of the dredged material on land. The second that is recommended is the extension of the trestles, the offshore port infrastructure.

Leck tells me that “by increasing the length of the terminals, you avoid dredging and dumping almost completely. But this option was never seriously considered, mainly because of its cost. That’s the greatest disappointment from this decision, because when you actually look at the cost involved and then compare it to the cost of the mine project, the railway and all the other stuff, it’s a fraction of the total. The GBRMPA and the government knew that there were much better options, much less damaging and yet still they approved something that could be avoided”.

When asked, the GBRMPA gave a very simple explanation : As a marine park authority, it doesn’t have the jurisdiction to impose a land disposal, much less an extension of port terminals. “Our legislative powers simply enable us to approve or reject a permit application for an action in the Marine Park, or to approve it with conditions”, said in a public statement Russell Reichelt, the chairman of the GBRMPA. “Based on the considerable scientific evidence before us, we approved the application for Abbot Point with conditions, on the basis that potential impacts from offshore disposal were manageable and that there would be no significant or lasting impacts on the Reef’s World Heritage values.”

In another statement, available on their website, the GBRMPA explains that as a deepwater port that has been in operation for nearly 30 years, Abbot Point is better placed than any other port along the Great Barrier Reef coastline to undertake expansion. Furthermore, the dredged material is composed of 60% sand and 40% silt and clay, according to the scientific testing they conducted. Still according to the report, none of it is toxic in any way to the environment.

To make sure the outstanding value of Great Barrier Reef will not be harmed in the process, the GBRMPA imposed the strictest conditions it had ever placed on a project of this type. Part of these conditions include a dumping site that is similar to the dredging site, about 40 kilometers from the nearest offshore reef but still in the World Heritage Area. The material will only be allowed to be placed in a defined four kilometer square site free of hard corals, seagrass beds and other sensitive habitat. The dumping will only occur step by step over three years, and exclusively between March and June (the austral autumn) which is outside of the coral spawning and seagrass growth period.

Despite these precautions, many Australians want to see a ban on dumping within the World Heritage Area. Due to the great public response the WWF Australia received, a legal fighting fund to challenge the decision in court has been created.

And it isn’t the only ongoing legal battle. Two board members of the GBRMPA are suspected of conflict of interest. Indeed, Tony Mooney works as an executive of Guildford Coal, a company that operates in north Queensland. The second one, Jon Grayson, owns shares of Gasfields Water and Waste services, a company that would largely benefit from the expansion projects of several ports along the coast. Various documents show that the pair helped approve several port developments. The results of the inquiry asked by Greg Hunt haven’t been made public at this point. Richard Leck sums it up: “Regardless of the conflict of interest, I wonder if it is appropriate to have someone on the Reef’s board that works for a coal company.”

Nonetheless, several external factors may change the deal regardless of these legal inquiries.

First of all, coal isn’t as good an investment as it used to be several years ago. Two of the world’s biggest banks, the American Goldman Sachs and the Swiss UBS, have published concurring reports on the subject, and it isn’t looking good for the Galilee Basin. “The window to invest profitably in new mining capacity is closing. We downgrade our price forecasts to US$85 the ton of coal in 2015” reports Goldman Sachs. According to another study, the mines of Queensland need a price of US$100 the ton or more to be viable.

Secondly, the Australian Senate has approved early March a non-binding mention asking the Environment Minister Greg Hunt to revoke his approval of the Abbot Point coal port expansion. “The Senate and the community are sending a strong message to the Abbott Government that dumping millions of tonnes of sludge in the Great Barrier Reef is unacceptable”, said Senator Larissa Waters.

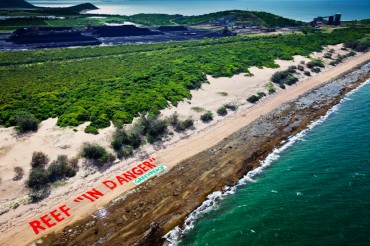

Finally, the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area is on the brink of being included on the List of World Heritage Sites in danger. Roni Amelan is the press officer for World Heritage issues at UNESCO: “At the moment, there is no way to know if the Reef will be put on the list of World Heritage in Danger or not. As requested, the Australian government has delivered a report on their progress to manage the Marine Park. The World Heritage committee will review the report, and in June when they meet in Doha they will take a decision.”

Being a moral authority, the World Heritage Committee doesn’t have the power to impose anything on any of the member states. UNESCO is quite helpless without the help and the cooperation of the country that requested the site to be inscribed on the list in the first place. The effects of being on the danger list are not clear, because each site is unique and requires unique actions. Roni Amelan notes that “there have been several cases where putting a site on the danger list has been very useful, in terms of raising awareness on problems and mobilising support.”

Being a moral authority, the World Heritage Committee doesn’t have the power to impose anything on any of the member states. UNESCO is quite helpless without the help and the cooperation of the country that requested the site to be inscribed on the list in the first place. The effects of being on the danger list are not clear, because each site is unique and requires unique actions. Roni Amelan notes that “there have been several cases where putting a site on the danger list has been very useful, in terms of raising awareness on problems and mobilising support.”

The consequences won’t be long in coming : “The Great Barrier Reef is regarded as one of the great marine wonders of our planet, Leck concludes. If it is placed on the endangered list, people will obviously think that the quality of the experience they would get there is not what they had planned.”

A fear that seems to be already felt by people living thanks to the Great Barrier beauties, as confirms Jacquie Sheils, a marine biologist and tour guide based in the Whitsunday Islands: “In the beginning everyone came because they wanted to see this great international icon. Now they come and they say they want to see the Great Barrier Reef before it dies. Up until about five, six years ago, you never heard that. Now you hear it every day.”

Want to learn more about the situation ? The GBRMA official website displays a lot of information and maps on the port expansion programs.