Red Flag

One year after the enthusiasm described in the chapter “Innovative solutions for global interest”, the bitter reality caught up with the people of Reunion Island.

The French volcanic island is currently surrounded by an untouchable ocean. Even on the hottest days, it is forbidden by law to go for a swim. This situation is unheard of anywhere else in the world.

Until recently, two beaches exposed to the Indian Ocean were protected by experimental nets. Unfortunately, the forces of nature proved too destructive and the structures are now badly damaged. Cut off from the open ocean by a fragile coral reef, the lagoon was the only other portion of coast offering a safe bathing area. But several juvenile bull sharks were spotted slicing through its waters. The red flag has since been raised, meaning a total ban on swimming all around the French island.

Worse, four additional surfers have been attacked by sharks in less than a year. The luckiest one only suffered a minor scratch, his board sustaining the full impact of the powerful jaw. Of the remaining three, two lost their lives due to a severe hemorrhage, while the last one will remain mutilated for the rest of his life.

Worse, four additional surfers have been attacked by sharks in less than a year. The luckiest one only suffered a minor scratch, his board sustaining the full impact of the powerful jaw. Of the remaining three, two lost their lives due to a severe hemorrhage, while the last one will remain mutilated for the rest of his life.

This brings the total to nine fatalities in less than six years. Each tragedy raises many more questions than it brings answers.

Yet, Reunion Island was once at the front guard of shark science. Starting in 2011, the ambitious CHARC program tagged and monitored 38 bull and 45 tiger sharks during five years. The project led by the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD) ended with the publication of the results, and since then research is at a standstill on the island.

As a marine biologist, Antonin Blaison was in charge of studying the sharks’ behavior during the IRD’s program. “I arrived in La Reunion in 2011, he remembers, right at the beginning of the shark crisis. After CHARC, the local fisheries were the only ones still doing sharks science. I was hired there in February of 2017 to develop the scientific aspect of the “Cap Requin” program.”

“Cap Requin” is the highly controversial shark culling program. A scientist amongst fishermen, isn’t it contradictory? “I saw an opportunity to redirect the program towards a more responsible one, answers Antonin Blaison. I want to show that we can associate a scientific program to a culling one. Science brings value to the fishing effort, and even though they are two different actions on the same species and problem, they share the same objective: to lower the risk of shark attacks.”

The young biologist would like to develop a new tagging and monitoring project for the two species of sharks. “If there is a new change in behavior in the next few years, we will find ourselves in the same situation as 2011. Utterly unable to explain what happened.”

Today, there are voices in Reunion Island asking to categorize the bull shark as an invasive species. For the scientist, “it wouldn’t help surfers get back in the water. Nor would it allow the understanding of the origins of the attacks. We are currently incapable of knowing how many sharks navigate the waters of the island.”

Today, there are voices in Reunion Island asking to categorize the bull shark as an invasive species. For the scientist, “it wouldn’t help surfers get back in the water. Nor would it allow the understanding of the origins of the attacks. We are currently incapable of knowing how many sharks navigate the waters of the island.”

According to Antonin Blaison, the best way to assess a population of fish remains to capture specimens. To be scientifically accurate, the effort needs to be constant all around the island and all year round, with consistent methods. “In the United States, he adds, an assessment of a population of bull sharks took ten years. With the crisis we are experiencing here in La Reunion, we can’t afford ten years of sitting and waiting.”

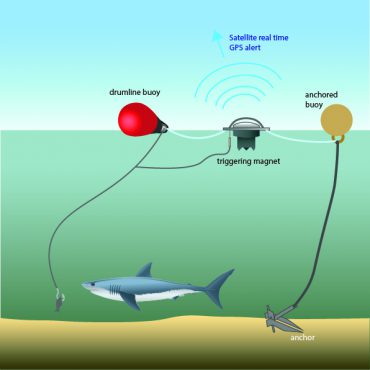

There are currently two fishing methods taking place in the waters of the French island. The first one is aimed at targeting sharks that are at a stone’s throw from the shore. Not all specimens will come close to the beaches and surf spots. The ones that do are faced with a series of fishing devices ingeniously equipped with a capture alert. They are the famous “smart drumlines”.

“The second objective of our action can be seen as a quantitative one, explains Antonin Blaison. It is aimed at reducing the population of sharks. In order to achieve this, the fishermen go one or two kilometers offshore and sink bottom-set longlines with at least 25 baited hooks.”

This combined fishing effort begun early this year, but was is on standby due to administrative and financial reasons. In January, an important staff shift took place at the fisheries, and war has been raging ever since. The new team accuses the old one of misuse of public funds. The vaults have been empty for several months, meaning no more fishermen are paid to go out and catch sharks.

It’s a hot topic of debate, to say the least. One of the strongest critic relentlessly heard about the “Cap Requin” program was the attribution of fishing rights. According to the objectors, the annual budget of around 800’000 euros was systematically promised to the same group of professional fishermen.

One of the main electoral promises made by the new team was the opening of the shark market to every fisherman on the island. In theory, an open market should be more competitive and efficient. But when the aim is to catch one of the sliest marine predators of the world, an animal capable of avoiding most traps laid out for him, the situation quickly gets out of hand. Only a handful of experts seem to be able to specifically target bull sharks.

David Guyomard was the former head of “Cap Requin”. With the help of Christophe Perry, a renowned fisherman of Reunion Island, he invented the smart drumlines. His employment at the local fisheries was terminated in March 2017, and he feels the frustration of a long and unfinished project. “When the new team took office, he tells me on the phone, they opened the shark fishing market to anybody who was willing. As it was expected, the fishermen mostly caught tiger sharks, and quite a lot of them. Only a few professionals, some of which were part of the old Cap Requin program, managed to catch a handful of bull sharks.”

The new fishing rules were as follow: Each boat was entitled to 200 euros for going out at sea, whether there was a hit or not. A text message was all that was requested to announce the campaign. If a targeted shark was caught, its meat was bought back at a price of four euros the kilo of tiger shark and ten euros the kilo of bull shark. This method is criticized by the old staff, led by Ludovic Courtois, former secretary general. Once the money dried out, a long and tedious procedure was launched to receive additional operating budgets. The current fisheries’ personnel confirmed that the boats will be able to get back out soon.

With these new rules, David Guyomard worries for the safety of surf spots where no drumlines are deployed: “When the new staff took office, the fishermen visibly lost all interest in the fishing zone of Saint Leu. No boat bothered to visit the area over the course of several weeks. At the end of April, Adrien was mortally attacked on the wave in front of La Pointe au Sel.”

With these new rules, David Guyomard worries for the safety of surf spots where no drumlines are deployed: “When the new staff took office, the fishermen visibly lost all interest in the fishing zone of Saint Leu. No boat bothered to visit the area over the course of several weeks. At the end of April, Adrien was mortally attacked on the wave in front of La Pointe au Sel.”

According to David Guyomard, his colleague Christophe Perry represented 50% of the program’s effectiveness. As project coordinator, he was constantly deploying the devices according to the most recent sightings. “The facts speak for themselves, says the former supervisor of “Cap Requin”. During the year and a half we were able to correctly work with our smart drumlines, from mid 2015 to early 2017, there were no attacks on surfers in the popular zone of Saint Leu, Trois Bassin and around.” The only accident that took place in this period was within the experimental nets of Boucan Canot. The red flag had been raised on this particular 27th of August 2016, because the structure’s integrity was compromised.

David Guyomard is convinced that the precise targeting of sharks visiting coastal hotspots, instead of offshore-large-scale fishing, is the way to go. On this topic, Australia’s best practice seems to confirm the theory: “I recently came back from a month-long trip to New South Wales, where I visited local scientists. They are currently using a network of smart drumlines, our invention developed here in Reunion Island, to catch sharks on specific coastal zones. Instead of killing the animals, they tag and release them further offshore.”

From Ulladulla to Ballina and all through Sydney, following one of the most surfed coast in the world, 50 smart drumlines are being deployed on key sites.

Further North, in the waters of the Gold Coast, Queensland, there are thousands of surfers enjoying the waves each and every day. “Yet, there are no attacks, says David Guyomard. It’s not for a lack of bull sharks, let me tell you this. There are large populations in the canals and on offshore sites. For the past 50 years, regular drumlines made out of rudimentary materials have been protecting the most popular beaches. Unfortunately, there’s is in important amount of bycatch. And it certainly doesn’t stop sharks to proliferate further offshore from the drumlines. In the end, it seems highly efficient to prevent attacks on swimmers and surfers.”

On the coast of New South Wales (NSW), the most recent attacks were attributed to juvenile great white sharks. An emblematic species protected by several international conventions, contrary to the bull shark.

Based on this fact, the powerful Department of Primary Industries (DPI) was tasked to develop the state’s shark management strategy. With an investment of 16 million Australian dollars (around 11 million euros) over five years, the DPI was able to develop effective instruments.

“In this part of Australia, says David Guyomard, they fish exclusively by day, which is the opposite of what we are doing in Reunion Island. This is probably why mostly great white sharks end up on the lines, as the bull shark is almost impossible to fish during the day. Once caught, the predator is tagged with an acoustic mark that can last a decade, and is then released further offshore. All of these animals can then be detected by a network of listening stations. After meeting with the DPI team in charge, they told me that swimmers and surfers don’t really use the automatic broadcast tools (editor’s note: there is a twitter account automatically updated each time a tagged shark is detected by a station). They are mostly reassured knowing that drumlines are deployed by day in front of beaches and surf spots.”

At the end of August 2017, the scientists overlooking the DPI shark management program informed the Australian journalists that “the smart drumlines could be more beneficial than previously thought”. It seems that once released, the tagged sharks swim further offshore. The DPI recently decided to add 50 smart drumlines in the waters around Byron Bay, Northern New South Wales.

Back in Reunion Island, there is no plan to stop the culling program and shift it towards a tag and release effort like it’s the case on the eastern coast of Australia. Even if the same tools are involved, the environment is extremely different and the targeted species aren’t the same. In this day and age, the public opinion is strongly against the killing of sharks. It has been proven that the apex predator plays a vital role in most marine ecosystems.

Back in Reunion Island, there is no plan to stop the culling program and shift it towards a tag and release effort like it’s the case on the eastern coast of Australia. Even if the same tools are involved, the environment is extremely different and the targeted species aren’t the same. In this day and age, the public opinion is strongly against the killing of sharks. It has been proven that the apex predator plays a vital role in most marine ecosystems.

In February of 2017, the surfing community and the ecologists of the whole world were flabbergasted by Kelly Slater’s surprise statement. Widely considered as the greatest surfer in history, he is especially respected for his numerous campaigns to protect the environment and the ocean in particular. Against all odds, a few days after yet another fatal shark attack in Reunion Island, he published a comment on Instagram calling for a cull in the waters of the French island. He added that “there is a clear imbalance happening in the ocean there. If the whole world had these rates of attack, nobody would use the ocean an literally millions of people would be dying like this.”

His social media went up in flames, and many environmentalist NGOs were left numb. A heinous flow of comment poured all over Kelly Slater’s pages. He was called a shark-killer, deserving nothing more than to be eaten alive the next time he went surfing. The scale of the scandal probably surprised the man himself, as he temporarily lost his status as an environmental activist.

Contacted to clarify his position, Kelly Slater answered by email that he is not in favor of the protection of a species that seems to have focused on eating people while its food source must be out of balance. “Also, he adds, I am not for ruining the environment that should naturally be there. I wonder if there actually is a solution that can work for both causes. At this point, I don’t believe there is.”

Wherever the topic was brought up on internet, the conclusions in the comment section were almost always the same: “the sharks are in their home ; we doesn’t belong there ; leave the sharks alone ; if the sharks disappear, the oceans will die and we will die…” A simplistic, black-and-white message that is easy to digest and repeat. Very few people actually tried to understand why Kelly Slater came to this conclusion. In the digital frenzy, one voice stood out.

Mark Healey is also a legend in the surfing community. The 36-year-old Hawaiian has made a name by riding the biggest and meanest waves of the planet. Like most watermen, he does not satisfy with a single specialty: he is also an accomplished free diver and spear fisherman. After spending most of his life in the ocean, he naturally got interested in marine biology, and sharks in particular.

Mark Healey is also a legend in the surfing community. The 36-year-old Hawaiian has made a name by riding the biggest and meanest waves of the planet. Like most watermen, he does not satisfy with a single specialty: he is also an accomplished free diver and spear fisherman. After spending most of his life in the ocean, he naturally got interested in marine biology, and sharks in particular.

“I spearfish since I am young, he tells me on the phone, and because of its dynamic, you end up being close to a lot of sharks. As I was exposed more often, I realized that my initial fear was a little unfounded. By taking them for what they actually were acting like, and get over the fear made up in my mind, I was able to spend time with fairly big individuals. I now have a really good idea of how to read sharks and their body language. What is interesting for the scientific community, is that I am good at getting close to them in their wild environment, away from feeding sites. Some species are highly susceptible to mortality rate when they get caught on a line. By tagging them with my spearhead, it’s one little sting and they go back to their day to day life.”

Considering his background, it would be safe to assume that Mark Healey opposes any shark culling program. Yet, he was one of the only to understand and back up Kelly Slater’s comment on the bull shark situation in Reunion Island. According to the Hawaiian surfer, there seems to be a “borderline unnatural situation there.”

“Don’t get me wrong, he adds, I don’t think that a culling idea applies to anywhere else in the world, at any time during my lifetime. In the waters of La Reunion, the bull sharks display a bad habit. They are highly migratory animals, so it’s possible they developed the habit of eating something bigger than their normal prey somewhere else. Nobody knows. But they are not an endangered species. I don’t understand how people can value the life of an animal that is plentiful in the world over a human life.”

That being said, Mark Healey does not think we should go out and kill them all. “The government has tried a lot of different things, he says. Obviously, they aren’t working. A solution needs to be found, besides making everybody live in fear and disconnected from the ocean.”

Most agree that there is some imbalance in the ecosystem of La Reunion, and that human activities are likely the reason for this situation. Kelly Slater and Mark Healey are part of a group of experienced watermen that encourage further actions. “Take Hawaii as an example, says Healey. We probably have the highest density of endangered species in the world. For the landmass, there are a lot of endemic species that are threatened by invasive plants and animals. Bad decisions were made in the past, but should we just leave everything alone, and let nature find balance? The native species will go extinct. Sometimes, if the initial problem can be traced back to man-made problem, it often takes a man-made solution.”

Most shark experts of the marine world are strongly against culling programs. William Winram is a freediving legend. Holder of various world records, he lends his extraordinary lung capacity and his knowledge of marine biology to numerous scientific programs around the world. With the non-profit organization “The Watermen Project” that he founded, Winram actively works towards shark conservation. “I am disgusted by surfers that want to kill sharks,” he tells me straight up.

William Winram, who is also a surfer, fully understands the issue: he was brought in to Reunion Island to consult in 2011, alongside Fred Buyle, fellow exceptional freediver. The two watermen dove all around the island while the shark crisis was only beginning. Six years and too many fatalities later, he tells me: “At that time, La Reunion didn’t present itself to be this incredibly healthy ecosystem. The question of why shark behavior shifted, we can only speculate. It might be explained by a significant decrease of the biomass in the general waters. The sharks then need to look for other candidates. I don’t know if anybody will be able to figure that out.”

William Winram, who is also a surfer, fully understands the issue: he was brought in to Reunion Island to consult in 2011, alongside Fred Buyle, fellow exceptional freediver. The two watermen dove all around the island while the shark crisis was only beginning. Six years and too many fatalities later, he tells me: “At that time, La Reunion didn’t present itself to be this incredibly healthy ecosystem. The question of why shark behavior shifted, we can only speculate. It might be explained by a significant decrease of the biomass in the general waters. The sharks then need to look for other candidates. I don’t know if anybody will be able to figure that out.”

According to the freediver, lack of knowledge certainly doesn’t justify the need to cull bull sharks. “I feel for anybody who has lost a family member, but can we please stop killing wildlife so that we can go and recreate in the ocean? I encourage people to stop surfing in Reunion Island. When I saw one particular surf break, considering the layout and the species of sharks, I told them they couldn’t pay me to paddle out. It’s tough for the locals. I met a lot of guys over the years that can’t live without surfing. They are better human beings because of it. It becomes an outlet. When you take that away, it’s the same as when you take away somebody’s anti-depressant. Potentially, it’s catastrophic for them.”

Winram regrets that the debate on Reunion Island is clouded by emotions. “Unfortunately, he says, we no longer live in harmony with the environment. We have lost our connection and our reverence. The health of the oceans is critical to our survival, as more than 50% of the air we breathe is manufactured somewhere at sea. Sharks are top predators, and every time we wipe out one of these species, we throw the ecosystem off balance.”

Abstinence may not be the only way. When the freediver visited La Reunion in 2011, he suggested to set up a team of shark guards. Today, they are known as “Vigies Requin Renforcées”. “I am very happy to see the surf guards up and running, says Winram. I think it is the most intelligent solution. It allows surfers to peacefully cohabite with these creatures in their home.”

The Vigies Requin are a group of young athletes that followed special training. They are now employed by municipalities to secure particular surf spots. When the meteorological conditions allow it, with at least 8-meter visibility underwater, they grab their mask, snorkel, flippers and jump in the water in pairs. They keep their head under the surface for several hours at a time, while on the surface, surfers can enjoy the waves with a complete peace of mind.

“We have totaled more than 700 hours of deployment without a single incident”, confirms Eric Sparton, the president of the surfing league of Reunion Island and supervisor of the Vigies Requin Renforcées program. “It’s true that we have the only structure that is operational all year round. The only factors that disturb our program are the sea conditions and its turbidity. There are some constraints, but it’s the reality for many things here in La Reunion. We are nonetheless looking forward to the complementary programs that are the experimental nets and the culling program.”

At the moment, there is a new reality in Reunion Island, and Eric Sparton summarizes it perfectly: “We need to understand that surfing, as we once knew it, is over. I see hundreds of people paddling out when the waves are good. I do believe in personal freedom, but they take the risk of dying each and every day.”

At the moment, there is a new reality in Reunion Island, and Eric Sparton summarizes it perfectly: “We need to understand that surfing, as we once knew it, is over. I see hundreds of people paddling out when the waves are good. I do believe in personal freedom, but they take the risk of dying each and every day.”

The surfing league works hard to put up a secure environment for all of those that are too passionate to abandon their sport. Of course, there is no such thing as zero-risk. “Several times, we had doubts, says Eric Sparton. It happened four times when we think there was a mass that could have been a shark, all of the surfers were evacuated in less than 30 seconds. The vast majority of the time, the predator is nowhere to be seen. Due to the number of hours we spent in the water, our program is clearly the most constant and experienced.”

I asked him if a tourist could get off the plane, rent a board and paddle out to a surf spot secured by the Vigies Requin. “It’s possible, answers Eric Sparton. First, he needs to sign up in one of the licensed clubs. Anybody can get a license and enjoy the safety of the Vigies Requin. It’s a beautiful way to acknowledge the work we have done. For the past three years, surfers have been able to get back in the waves, and the least they can do to thank us is to get a license that costs 50 euros per year. This way, we will be able to extend our program to other municipalities. There is a project for Saint Leu, l’Étang-Salé, Saint Pierre, Manapany and Saint Benoît.”

Reunion Island is still the hub of fantastic surfing potential. At the last world championship in Biarritz in May of 2017, the medals were won by the French team led by Reunion surfers. But Eric Sparton worries about the generation gap that the shark crisis has been digging for six years: “Within the league, we are all too aware of this fact. But I am confident and we have a plan. The most important thing right now is to reopen the surfing schools. They are the ones that bring us all of the beginners, through initiations. These private schools are the solution to replenish the higher levels. This is what we are actively working towards. It would also create jobs in a badly hit sector.”

According to the last estimations, local tourism is doing rather well. The visitors are coming back in greater numbers than during previous years. The shark crisis has made headlines in many international newspapers, so the tourism office of Reunion Island had to concentrate its marketing strategy on the lush mountains and stunning hiking routes the island has to offer. A safe surfing environment would surely play a role in the economic recovery of one of France’s region most badly hit by unemployed.

To be continued.