Of Islands and men

Rita Bancoult was born in 1928 on the atoll of Peros Banhos, in the northern part of the Chagos Archipelago. Her parents and grandparents were born on the same group of islets, and lived their entire life on the 9.6 square kilometres of land that hardly make it over the blue waters of the Indian Ocean. Rita was a chagossian, a native of Chagos.

She didn’t have an easy life.

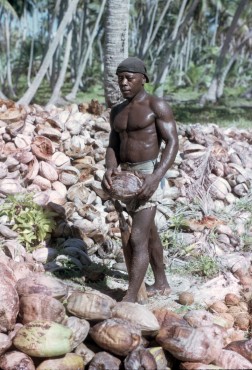

A part from the villages’ designated fisherman, everyone she knew worked on the coconut plantations. From the dried coconut flesh, or copra, a fine coconut oil was made and sold worldwide. The islands became known as the “Oil Islands”, and the islanders used their bare hands to husk their weekly quota of fruit, to build the plantation’s infrastructures and their own houses.

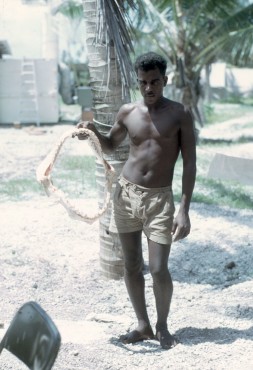

Kirby Crawford, who was one of the first Americans to visit the island of Diego Garcia at the end of 1968, had the brilliant idea to bring a Canon FT 35mm camera to shoot the daily lives. « The plantation operated without electricity, says Crawford. They had one small Honda truck, and a tractor. Other than that, most everything was done by hand. Copra production was in full swing and plantation workers lived all over the island ».

Kirby Crawford, who was one of the first Americans to visit the island of Diego Garcia at the end of 1968, had the brilliant idea to bring a Canon FT 35mm camera to shoot the daily lives. « The plantation operated without electricity, says Crawford. They had one small Honda truck, and a tractor. Other than that, most everything was done by hand. Copra production was in full swing and plantation workers lived all over the island ».

The Creole workers were employed on individual contracts valid for one to three years at a time, and were paid in cash wages and “in-kind” benefits. « You had your house, Rita recalls, and you didn’t have rent to pay. With my ration, I got rice each week, flour, oil, salt, dhal, beans. We planted pumpkin, greens. And we had chickens and ducks. Life there paid little money, very little. But it was the sweet life ».

Fresh water came from shallow wells, and the plantations companies provided food and tobacco rations, a small dispensary for basic medical attention, and even a school. Supplies on the islands came by way of the sea, on board the M/V Nordvaer, only four times a year. The ship came in with hired workers from Mauritius and the rations. It departed the Chagos with the islands’ coconut production as well as people visiting their family or seeking serious medical attention that was only available in Port-Louis, 2’200 kilometres away.

At the end of 1967, Rita’s three year old daughter Noellie badly injured her foot. The Peros Banhos’ nurse told the family that she needed surgery, in the nearest full-service hospital, a four to six days open ocean journey. The family had to wait two excruciating months for the M/V Nordvaer to come back, and when they all finally arrived at the Port Louis hospital, the doctors operated only to see that the injury went untreated for much too long. Noellie died soon after.

Two months after the tragedy, when the M/V Nordvaer was about to leave on its return journey, Rita walked to the office to arrange the family’s trip back home. She almost fell backwards when she was denied. « Sorry ma’am, your island has been sold, the ship’s representative told her. You will never go there again ».

Before 1966, the islands were privately owned. But one by one, they were all purchased by the BIOT who then leased them back to the coconut plantation companies. After May 1967, the BIOT issued a set of measures to begin with the depopulation of the Chagos Archipelago, to slowly make way for the American military base. The easiest way was to prevent the Chagossians to come back after they temporarily left the islands, which they were free to do since emancipation.

Even when the plantations started running low on workers in 1968, the BIOT refused to allow Chagossians to come back. The delivery of mail between Mauritius and Chagos was suspended, and there was no telephone service at the time in the archipelago. News of the Chagossians stranded on Mauritius did not reach their friends and families. To replace the missing workforce, the BIOT allowed the employment of Seychellois on temporary contracts.

With the beginning of the construction of the military base, and the uncertainty of the future of the islands, the BIOT gradually reduced the available services. Less and less supplies were loaded on the ships heading out to the Chagos. Rice, flour, medication and other basic goods started to miss. The schools and hospitals closed.

Some Chagossians decided to leave, and try their luck in Mauritius where a difficult situation was awaiting. Following the country’s independence, unemployment and insecurity were common. Other Chagossians were tricked and boarded the ships without knowing that it was a one way ticket, but many weren’t at all ready to leave the birth and burial place of their ancestors. Something had to be done to get rid of the last resistance.

Some Chagossians decided to leave, and try their luck in Mauritius where a difficult situation was awaiting. Following the country’s independence, unemployment and insecurity were common. Other Chagossians were tricked and boarded the ships without knowing that it was a one way ticket, but many weren’t at all ready to leave the birth and burial place of their ancestors. Something had to be done to get rid of the last resistance.

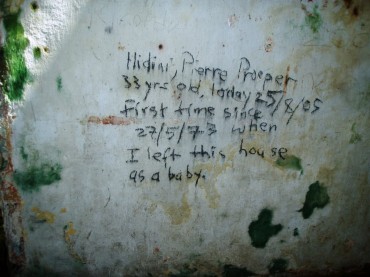

In 1972, when Bernadette Dugasse was two years old, she was part of the last group to be forcibly expelled from the main island of Diego Garcia. « My mother and my adoptive grand-mother told me the story. We were forced onto ships at night time. We could only bring what we could carry, which wasn’t a lot. And we didn’t know where we were going! Nobody told us the destination. My family and I were put on an overcrowded boat to the Seychelles, but most of the Chagossians were deported to Mauritius. Upon arrival, nobody was there. We were left on the docks, with nothing but our clothes on our backs ».

The disappearing Creole community witnessed the most violent episode of their deportation when British agents and U.S. troops on Diego Garcia rounded up the Chagossians’ pet dogs into sealed sheds and executed them with engine fumes. The owners who were awaiting deportation watched the whole traumatising scene before boarding the boat to Mauritius, where they were parked into the worst slums of their new island.

Clearly violating four Human Rights articles, as well as the United Nations rules on decolonisation, the British and American plan was able to succeed for two reasons. The first was that it was kept secret until it was too late to react. The second was that British officials « maintained the fiction that the inhabitants of Chagos were not a permanent or semi-permanent population », as proposed at the time by the Foreign Office legal adviser Anthony Aust.

Aust also wrote that « we are able to make up the rules as we go along », deliberately classifying the multiple generation Chagossians as a « floating population » of « transient contract workers » with no connection to the island. The truth was very well known in London, as a written note at the Foreign Office was uncovered saying that « along with the birds [on Chagos] go some few Tarzans or Men Fridays whose origins are obscure, and who are being hopefully wished on to Mauritius. »

In 1971 in Mauritius, the government started noticing an awful lot of new people that were mostly illiterate, spoke their own kind of creole and couldn’t find a job in the copra industry which simply didn’t exist there. For many years, absolutely nothing was done to assist the refugees.

As a compensation for this forced resettlement, the British and Mauritian government came to an agreement. £650’000 were paid to Mauritius to help the “relocation” of Chagossians plantation workers. The money was kept for 6 cruel years, inexorably losing value to inflation. It’s only in 1978 that it was distributed back to the true exiled Chagossians. It proved to be a difficult task.

Indeed, how many of the workers could be considered temporary hired, and how many were considered natives? There is still today some sort of dispute on the numbers. Richard Dunne is a British lawyer that visited Diego Garcia in 1979 for two days while serving the royal NAVY. « I didn’t know anything about the archipelago and its history at the time, Dunne told me. When I learned what happened, I had to get involved. First, with my colleague Richard Gifford we researched the numbers and wrote the article “A dispossessed people: the depopulation of the Chagos Archipelago“.»

The article that was first published online in 2012 says that « The size and nature of the Chagossians were deliberately manipulated and concealed by British colonial officials in order to avoid scrutiny by the United Nations. By comparing the best available contemporary records and government archives, we conclusively demonstrate that the policy of the British Government drove between 1’328 and 1’522 Chagossians into exile and poverty on Mauritius, and a further 232 on the Seychelles. »

The article that was first published online in 2012 says that « The size and nature of the Chagossians were deliberately manipulated and concealed by British colonial officials in order to avoid scrutiny by the United Nations. By comparing the best available contemporary records and government archives, we conclusively demonstrate that the policy of the British Government drove between 1’328 and 1’522 Chagossians into exile and poverty on Mauritius, and a further 232 on the Seychelles. »

In the slums of Mauritius, where drugs and alcohol decimated entire families, the Chagossians were barely capable of reimbursing their debts with the 1978 compensation. No one in the Seychelles received compensation. Their plight and deplorable living conditions slowly made their way to international ears. The Washington Post was the first Western press to acknowledge the story in a 1975 piece, describing the people from Chagos as living in « abject poverty ».

Once the story was out, the Chagossians found the strength and the help to reorganise into communities. One of the first groups to file suit against the United Kingdom was led by Michel Vincatassin. Michel was the only Chagossian who had the idea to establish a paper stating that he was Diego Garcian, and that his family had always worked and lived in Diego. With the help of Gaetan Duval, the head of the Creole Party in Mauritius, he sued the U.K. for illegal exiling.

After years of legal battle, Michel Vincatassin dropped his lawsuit in 1982 in exchange for 4 million pounds, once again to be paid to the Mauritian Government who promised to distribute the money and additional land to the Chagossians in exile. In his 2013 essay “A Brief History of the Ilois Experience”, Ted Morris writes: « The agreement required all who received the 1982 Compensation to sign or thumbprint an affidavit called a Renunciation Form stating that this was the final settlement for any claims on the Chagos. This was to prevent endless individual lawsuits and claims for years to come, although in the end this did not stop the seemingly endless series of lawsuits filed against the United Kingdom in the 21st Century. Of 1’579 eligible Ilois, 12 people initially refused to sign or thumb the papers, including Vincatassin ».

Robin Mardemootoo, a Mauritian lawyer who represented the Chagossians, stated: « It was entirely improper, unethical and dictatorial to have the Chagossians put their thumbprint on an English legal drafted document. Most of them couldn’t read nor speak any English, let alone legal English. To receive the money, they were basically asked to renounce all of their rights as human beings».

Robin Mardemootoo, a Mauritian lawyer who represented the Chagossians, stated: « It was entirely improper, unethical and dictatorial to have the Chagossians put their thumbprint on an English legal drafted document. Most of them couldn’t read nor speak any English, let alone legal English. To receive the money, they were basically asked to renounce all of their rights as human beings».

The Chagossians didn’t read nor speak English, but they were in fact British citizens. Under the British Nationality Act of 1948, anyone ever born the Chagos was a “British Dependent Territories Citizens”, although this wasn’t publicised and not well understood by the Chagossians. Between 2001 and 2002, many Chagossians claimed the English passport and left Mauritius for the United Kingdom.

Bernadette Dugasse now lives with her husband and children in Thornton Heath, a grey district south of London where the contrast with her birthplace could not have been starker. « I think that when the British government gave us the citizenship, they thought we would stay in Mauritius and the Seychelles. They made a big mistake, because we came and now they don’t know what to do with us. We are not treated like everybody else. People from Pakistan are given council houses, receive benefits. But the Chagossians have to work like slaves for the least expected jobs, like cleaners and carers », Bernadette told me on a cold November afternoon.

Still in search of a job to help pay rent, Bernadette volunteers for the U.K. Chagos Support Association which actively calls for a right to return. She helps advising people who need to fill up English legal documents. When I ask her why they are several associations, and not a single most effective one, she answers: « The Chagos Support Association and the Chagos Refugee Group don’t see eye to eye anymore. They stopped communicating and are even fighting one another. The CRG is led by Olivier Bancoult, Rita’s son. It’s in his name that all the legal actions are taken, and he is calling for a settlement in the northern islands, where he was born. I was born on Diego Garcia, and I will never agree for anything else than a full right of settlement where we want and when we want. I don’t want to live in the northern atolls where I didn’t feel any connection ».

Olivier Bancoult and his lawyers won their first legal battle in November 2000. Two years of hearings were necessary, and finally the England and Wales High Court of Justice ruled that the expulsion of islanders was illegal, further condemning the wrongdoings. After 30 years of struggle, the Chagossians had finally won and were preparing to go home. Bancoult describes that day: « I will never forget that feeling of coming out of the court with a victory. A small people won against a big power ».

Olivier Bancoult and his lawyers won their first legal battle in November 2000. Two years of hearings were necessary, and finally the England and Wales High Court of Justice ruled that the expulsion of islanders was illegal, further condemning the wrongdoings. After 30 years of struggle, the Chagossians had finally won and were preparing to go home. Bancoult describes that day: « I will never forget that feeling of coming out of the court with a victory. A small people won against a big power ».

The suspense lasted less than four years, during which a game of bureaucratic ping pong took place. The English blamed the Americans for their refusal to follow the ruling, and Washington blamed London for denying the permission. Robin Mardemootoo summarises: « It’s an arrangement between them to treat this problem as a ping pong ball. And it’s terrible because by the time the ping pong game is over, there will be no Chagossians left ».

The confusion was abruptly stopped by a royal decree. An aged-old power still invested in the Queen and called an “Order in Council”. The same trick was played in 1965 by the government of Harold Wilson to secretly expel the Chagos Islanders. In June 2004, the Order in Council stated without a question that “no person has the right of abode in the British Indian Ocean Territory”, thus bypassing the parliament and the High Court.

Will Olivier Bancoult ever be able to bring his mother Rita back to her atoll? The case was brought several more times by his lawyers in front of the English justice, the American justice and even in front of the European Court of Human Rights. Never were they granted a second victory.

However, that might change with the publication of the “Feasibility Study for the Resettlement of the British Indian Ocean Territory” issued by KPMG, one of the largest consulting companies in the world. The final report hasn’t been officially published yet, but the 82 pages draft was made public in November 2014. « There are no insurmountable legal obstacles that would prevent a resettlement on BIOT », says the report, further outlining that it would prove challenging for Chagossians to go back, but certainly not impossible. Still according to the report, special care should be taken towards the future fishing practices in this pristine environment, as well as building methods that need to be sustainable on such fragile fragments of land. Diego Garcia is clearly the most realistic island option in the event of resettlement. It has the size to welcome hundreds if not thousands of Chagossians, and has developed ease of access with the U.S. military base. But smaller islands to the North are also viable solution that could welcome ecotourism resorts, and their Chagossians employees.

However, that might change with the publication of the “Feasibility Study for the Resettlement of the British Indian Ocean Territory” issued by KPMG, one of the largest consulting companies in the world. The final report hasn’t been officially published yet, but the 82 pages draft was made public in November 2014. « There are no insurmountable legal obstacles that would prevent a resettlement on BIOT », says the report, further outlining that it would prove challenging for Chagossians to go back, but certainly not impossible. Still according to the report, special care should be taken towards the future fishing practices in this pristine environment, as well as building methods that need to be sustainable on such fragile fragments of land. Diego Garcia is clearly the most realistic island option in the event of resettlement. It has the size to welcome hundreds if not thousands of Chagossians, and has developed ease of access with the U.S. military base. But smaller islands to the North are also viable solution that could welcome ecotourism resorts, and their Chagossians employees.

Finally, the report recommends a small-scale pilot resettlement that will act as test, followed by a medium scale resettlement if everything goes according to plan. The initial cost for the British taxpayer would be between 54 and 370 million pounds, depending on the different scenarios, and a further recurrent annual cost between 4 and 21 million pounds.

Returned Chagossians would be able to work for the military base, for the growing administration of the islands, in building the infrastructure, on a new coconut plantation, or in the fishing industry. Although fishing for money could prove complicated. Indeed, Diego Garcia is trapped since 2010 in a fully protected no-take marine park the size of France. As we will see, controversy surrounds the largest marine reserve in the world: the Chagos Marine Protected Area.