Diving, until saturation

1st of June, 2014 – In the warm and crystal clear Caribbean waters, just a few kilometres offshore from Florida’s coast, a crew of 9 divers is slowly sinking towards the depths of the sea. Their destination is lying 20 metres under the surface: “The Aquarius”.

Tightly anchored to the seafloor, this horizontal metallic cylinder long of 13 meters and covered in concretions is to this day the last remaining underwater habitat in the seas and oceans of our planet.

At the head of the mission is none other than the grandson of the legendary French marine exploration Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Fabien Cousteau is 46 years old, and as he leads his crew through the habitat’s airlock, he sets the beginning of “Mission 31”, an experiment of underwater living that will last 31 days and 31 nights. Officially, the crew of nine people will take advantage of this time to observe and analyse the effects of climate change on the corals of the Caribbean Sea.

At the head of the mission is none other than the grandson of the legendary French marine exploration Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Fabien Cousteau is 46 years old, and as he leads his crew through the habitat’s airlock, he sets the beginning of “Mission 31”, an experiment of underwater living that will last 31 days and 31 nights. Officially, the crew of nine people will take advantage of this time to observe and analyse the effects of climate change on the corals of the Caribbean Sea.

Prior to their arrival, the Aquarius was equipped with a top-notch communication system, and more cameras than there are divers. Presented as a world first, this adventure will be recorded 24/7 as the team will try to push the limits of life underwater. But is this experiment really the first of its kind?

The team of OCEAN71 Magazine decided to understand why men, who set foot on the moon and are capable of living in space for extended periods of time, seem unable to live below the surface of our seas and oceans.

###

52 years ago, 7th of September 1962 – In the bay of Villefranche-sur-mer, situated on the French Riviera, a team is at work on the deck of a discreet boat named Sea Diver. There are no video cameras here, and of course no smartphones nor wireless internet… A few photographers are nonetheless ready to capture either a world first or a human tragedy. This is a time when colours haven’t yet made their way to our television sets, seven years before Armstrong’s small steps on the bright side of the moon.

The owner of the ship and head of mission is an American called Ed Albert Link. The matters are serious, and he is focused on every action that is taking place on the deck of his ship. If mistakes are made, it can mean the death of a young man. Even if he is worried, he doesn’t let the crew see his emotions.

The owner of the ship and head of mission is an American called Ed Albert Link. The matters are serious, and he is focused on every action that is taking place on the deck of his ship. If mistakes are made, it can mean the death of a young man. Even if he is worried, he doesn’t let the crew see his emotions.

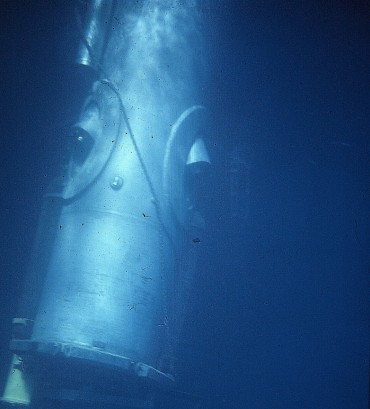

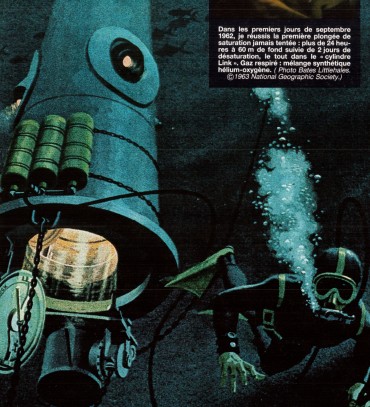

After having developed the very first flight simulator, Ed Link is about to tackle a new challenge. The goal of that particular day is to encapsulate a man in a reinforced aluminium cylinder of 3.3 metres long and 90 centimetres in diameter, and sink the bundle to 60 metres below the surface of the Mediterranean. This experiment is the very first recorded attempt to create an underwater habitat, even if in this case the cylinder is so narrow that a grown man cannot stretch his legs out.

The theoretical phase of the “Man in the Sea” program, with the help of the US Navy, was about to move into the practical stage. Link was finally going to answer a question that had been lately obsessing him: Is it possible for a man to live and perform tasks at the bottom of the sea? The army, for its part, was interested in knowing if the technology would allow them to rescue a team trapped in a sunken submarine.

To answer these questions, the engineers had designed and built the habitat. All they needed now was a volunteer. Robert Sténuit, a Belgian now aged 81, hasn’t forgotten one bit about what ended up being the experience of his lifetime: “Was it my goal to become a pioneer? No, I don’t think so. I was obviously looking to accomplish a feat, but if Link’s experiment proved to be successful, I was going to have access to all the wrecks in the world. All those sunken treasures that were beyond the reach of my diving friends would suddenly become reachable by us, and us only…”

To answer these questions, the engineers had designed and built the habitat. All they needed now was a volunteer. Robert Sténuit, a Belgian now aged 81, hasn’t forgotten one bit about what ended up being the experience of his lifetime: “Was it my goal to become a pioneer? No, I don’t think so. I was obviously looking to accomplish a feat, but if Link’s experiment proved to be successful, I was going to have access to all the wrecks in the world. All those sunken treasures that were beyond the reach of my diving friends would suddenly become reachable by us, and us only…”

On Friday the 7th of September 1962, young Sténuit at the age of 29 enters the tiny metallic cylinder that had been previously put in the water. He glances at Link and the crew of the Sea Diver one last time, and closes the hatch of what is supposed to be his home for the next 24 hours. Maybe more if the conditions allow it, and less if the experiment goes wrong.

“You know, it was another era. Before climbing in the cylinder, my only experience was 10 years of scuba-diving. I hadn’t done any psychological training. Nothing of that sort existed at the time. I knew I wasn’t claustrophobic, that’s all…” simply adds Sténuit.

Although numerous tests had been done on land to simulate tank diving, the rise of atmospheric pressure and various other parameters, Ed Link couldn’t possibly know for sure if the young diver would come back alive from the experiment. The sea can be capricious and complex to understand. Back then and still to this day.

The tiny underwater habitat was starting its slow descent into the blue of the Mediterranean.

At last, the silence was broken by a voice in the microphone:

At last, the silence was broken by a voice in the microphone:

“Robert, can you hear me? Is everything okay? Do you see anything?” Inside his cylinder, Sténuit is equipped with a wire that allows communication with the surface. Behind three tiny portholes, the Belgian diver can see the light diminish, and feel the humidity rapidly rising. It is a modest habitat, nonetheless Link thought to provide it with a small inside light, as well as a heating system to face the change of temperature.

The descent finally stops at 60 metres below the surface, and straight away several problems need to be addressed. First the pressure. At the surface, the ambient pressure is of one bar. 60 metres deep, the weight of the water on any given structure such as Link’s cylinder is of seven bars. To allow Sténuit to exit the habitat without having water flowing in, the inside pressure has to be identical to the outside. To stay dry, the diver sets the pressure on seven bars with the help of the crew. Seven kilos are now pressing against every square centimetre of his body. Immediately the cold and damp air becomes very heavy, but not unbearable.

Furthermore, at a depth of 60 metres, simply breathing remains one of the biggest challenges. On Earth, we inhale an mix of gases that is mainly composed of nitrogen and oxygen. The problem is that with the pressure found at the depth of the 1962 experiment, the surface air becomes toxic. Firstly, it is the nitrogen that is harmful at 30 metres deep. Then at 70 metres deep, it is the oxygen that becomes poisonous. Hyperoxia is unavoidable. To put it simply, the deeper it gets, the more dangerous it becomes to breathe surface air. The only possible solution is to invent a concoction of different gases.

Back in the “Link Cylinder”, Sténuit is breathing a mixture of helium (97%) and oxygen (3%), which in theory allows him to remain for 24 hours at a depth of 60 metres.

But that is not the point of the experiment. Now the young diver is supposed to exit the chamber, wander in the sea and perform tasks around the habitat. “At the time, we weren’t interested in observing corals… I had enough on my plate with the cylinder’s technical problems” recalls Sténuit.

But that is not the point of the experiment. Now the young diver is supposed to exit the chamber, wander in the sea and perform tasks around the habitat. “At the time, we weren’t interested in observing corals… I had enough on my plate with the cylinder’s technical problems” recalls Sténuit.

He gets ready and prepares the long hose that will still allow him to breathe as he exits the cylinder. As he starts inhaling through the tube, he smiles at the thought of the inventor of this revolutionary device, who is at the very same moment working on another type of underwater habitat, only a few kilometres away from him. This inventor’s name is Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

As Sténuit is experimenting underwater life at a depth of 60 metres in the bay of Villefranche, Belgians and Americans are a week ahead on French explorers.

Exactly seven days later, the 14th of September 1962, Cousteau will sink “Diogène” at 10 metres below the surface in front of Marseille. His very first underwater habitat 5 metres long and 2.5 metres in diameter was designed to welcome two divers for a whole week, at the foot of the Frioul Islands. Unlike Link’s experiment that pretty much went completely unnoticed, Cousteau’s project gained immediate international media coverage.

“The mission named Precontinent I took place at ten metres below the surface, explains Robert Sténuit. We perfectly knew that at this depth, one can spend his whole life without being the least bit inconvenienced. This is knowledge we’ve had for several hundred years. I don’t have a problem with Cousteau – the following work he did during the Precontinent II mission was very serious – but his strength at the time was to perfectly know who to deal with journalists and publicity… because he badly needed the financial support! The big difference with his experiment, is that ours with the Americans at Villefranche was done for a purpose that was purely scientific, and with no other money than Ed Link’s”.

Back in the tiny metallic cylinder, the hours pass. After having spent 26 hours at 60 metres deep, the experience of Ed Link and his team is announced successful. What was proven was that a man can live and work deep below the surface of the seas. But sooner or later, a diver has to come back up, and after going that deep, it certainly is the most dangerous part of every dive: the decompression.

Back in the tiny metallic cylinder, the hours pass. After having spent 26 hours at 60 metres deep, the experience of Ed Link and his team is announced successful. What was proven was that a man can live and work deep below the surface of the seas. But sooner or later, a diver has to come back up, and after going that deep, it certainly is the most dangerous part of every dive: the decompression.

When the gas is deeply inhaled, it dissolves through the lungs into the blood and the tissues of the human body. During the ascent, if done too rapidly, the dilatation of the gas can form microbubbles in the blood and can cause irreparable damages to vital organs by blocking the blood flow. When done the right way, a decompression prevents the formation of these dangerous bubbles. In theory, a long dive equals a long period of decompression.

Although this is no longer the case after a certain limit. Ed Link’s experience with Robert Sténuit was following the sensational discovery made 5 years early by a captain of the US Navy. In 1957, George F. Bond noticed on the rats of the “Project Genesis” that the time needed for a decompression only depends on the depth of the dive, and not on its length. Still in theory, Sténuit could have stayed several days or even weeks at a depth of 60 metres, yet the period of decompression would have been the same as for his 26 hours.

“Thanks to the diving technique of saturated gas, my 26 hours at 60 metres resulted in 49 hours of decompression in the cylinder, first at sea then lying on the deck of the boat. According to the calculations, if I had dived 26 times on hour in a row at the same depth, the decompression time should have been multiplied by 15… with 26 times the risk of an accident during each ascent” explains the retired diver.

Past the 75th hour, the young man finally crawled out of this incredible underwater adventure, exhausted but alive. In the race to conquer the world below the surface, the Americans won an important battle against the French.

Past the 75th hour, the young man finally crawled out of this incredible underwater adventure, exhausted but alive. In the race to conquer the world below the surface, the Americans won an important battle against the French.

“At the time, there was absolutely no possible collaboration with Cousteau. Either you worked with him, or against him. You can say there was some kind of healthy competition. It was the beginning of a great adventure!” exclaims Robert Sténuit, the very first aquanaut in the history of mankind.

The second chapter of this investigation will be published Friday 20th June 2014

NOTA © The cover photo was taken by Stephen Frink