Highway to hell

On Tuesday September 19th, 2011, horror and division creep up on the once peaceful and harmoniously multicultural Réunion Island.

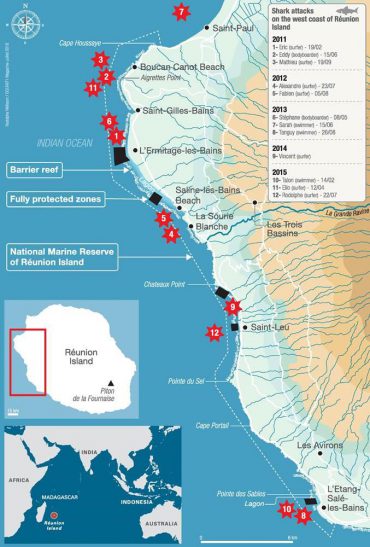

Mathieu Schiller, 32-years-old bodyboard champion, talented surf instructor and loved member of the community is killed at three p.m. on a sunny afternoon, just a few meters away from Boucan Canot, the most iconic beach on the island. His friends desperately try to pick his body up after the attack, but waves keep breaking on the group and Mathieu, unconscious and badly wounded, slips away. The witnesses later say they saw several sharks. In the evening, a team of professional divers equipped with “shark shields”, a magnetic repulsive device, go looking for the body, but are soon forced back on the boat by a three-meter-long agressive bull shark. The divers reluctantly abandon the mission. Mathieu Schiller’s remains are claimed by the unyielding Indian Ocean, never to be found again. Fear and speculations spread like wildfire. It’s the beginning of the “shark crisis”.

Spontaneously, a crowd gathers around the life-savers building in Boucan Canot, and tension is dangerously bubbling up to breaking point. Mathieu’s death is already the second fatal accident on west coast in as few as four months. Friends and families need explanations to this dramatic increase in shark attacks on what used to be perfectly safe surf spots. The then deputy mayor of Saint-Paul, Huguette Bello, is present and people start shouting at her while she answers a journalist’s questions. She says that Réunion Island’s ancestors always forbade their children from going swimming in the dangerous waters of this part of the coast. As a “zoreil” surfer, visibly traumatized by Schiller’s death a few hours earlier, calls her out to say that he has been living here for twenty years and never saw such problems, she replies: “I have been living here for the past 60 years, mister, this is my island.”

Spontaneously, a crowd gathers around the life-savers building in Boucan Canot, and tension is dangerously bubbling up to breaking point. Mathieu’s death is already the second fatal accident on west coast in as few as four months. Friends and families need explanations to this dramatic increase in shark attacks on what used to be perfectly safe surf spots. The then deputy mayor of Saint-Paul, Huguette Bello, is present and people start shouting at her while she answers a journalist’s questions. She says that Réunion Island’s ancestors always forbade their children from going swimming in the dangerous waters of this part of the coast. As a “zoreil” surfer, visibly traumatized by Schiller’s death a few hours earlier, calls her out to say that he has been living here for twenty years and never saw such problems, she replies: “I have been living here for the past 60 years, mister, this is my island.”

This sentence will quickly become the symbol of a ramping division, hardly ever voiced in public, but present since the dark colonial past of the island and its sad history of slavery. Surfing is wrongly considered as a elitist sport, enjoyed by the wealthiest and whitest part of the population. Some of the creoles that live on the hills, far away from the coast and its beautiful but expensive beaches, do not agree with “public money being spent a small group of white surfers. They don’t belong here. If they don’t like it, they can go back to Biarritz.” Some people started seeing the bull shark as a true local of Réunion Island, swimming in its rightful territory. Thus, the marine predator was symbolically getting a karmic revenge by targeting white colonial surfers.

A few days after Mathieu Schiller’s traumatic death, pressure is on the shoulders of the Prefect to allow the first official shark culling campaign. He autorises the capture of “no more than 10 predators known to be dangerous to men”. Large tiger sharks and bull sharks are targeted and a single specimen is caught: a 2.5-meter-long bull shark, whose stomach content clears from all wrong-doing.

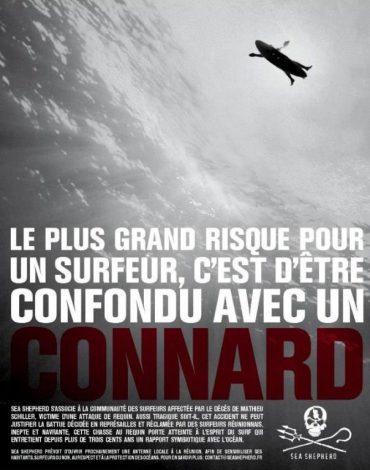

In the media around the world, this campaign is presented as a massacre, and the fierce spotlight of controversy suddenly shines right at Réunion Island’s surprised face. Almost overnight, and to the islanders’ great concern, several nature conservancy associations join the debate. The French branch of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society leads the pack. Through its website and social media pages, this non-governmental organization, mainly known for its spectacular actions against the Japanese whaling fleet in the Antarctic Ocean, begins actively communicating in favor of shark conservancy. In recent years, the apex predator’s struggle against over-fishing and loss of habitat became the symbol of ocean protection.

In the media around the world, this campaign is presented as a massacre, and the fierce spotlight of controversy suddenly shines right at Réunion Island’s surprised face. Almost overnight, and to the islanders’ great concern, several nature conservancy associations join the debate. The French branch of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society leads the pack. Through its website and social media pages, this non-governmental organization, mainly known for its spectacular actions against the Japanese whaling fleet in the Antarctic Ocean, begins actively communicating in favor of shark conservancy. In recent years, the apex predator’s struggle against over-fishing and loss of habitat became the symbol of ocean protection.

“We were fiercely and suddenly attacked on Facebook, says Patrick Flores, the assistant mayor of Saint-Paul and coach of France’s surfing team. As we were mourning the loss of our son and brother, all these people were posting insulting and hateful comments aimed at our community on the NGO’s pages. We weren’t organized, and it struck us hard.” Open warfare began. Countless posters, petitions and formal complaints were shot from one side to the other. This communication war is still raging today.

Two enemies fight through keyboards and computer screens: on one side, the various ecological NGOs are accused of putting the life of a marine predator over the life of local children. On the other, surfers are criticized for demanding the eradication of all sharks in the world. Florentine Leloup is the president of the French association Shark Citizen. She spent several years on the island to unravel the roots of the crisis and work towards tangible solutions. She ended up in the middle of the crossfire. “Without Facebook, she says, the organizations from mainland France would have never heard about the situation in Réunion Island. All these NGOs only reacted when official declarations were made by the prefecture, the region and the fishing committee. All three seriously lack communication skills, whereas the NGOs truly excel in this area. The battle was uneven.”

The president of Shark Citizen closely looked at each press release made by Sea Shepherd and the subsequent reactions from the public of Réunion Island. She quickly realized that the NGO always communicated during already tense moments for the local population. “Consequently, she explains, these posters or press releases were sort of the last straw that broke the camel’s back. People started to want to go and kill some sharks themselves, since the public authorities wouldn’t or couldn’t do it. These were common people who were holding back, until they were insulted on the internet by ignorant foreigners who had no idea of the reality on the ground.”

In real life, far away from the toxic computer screens, things started to cool down at the beginning of 2012. With too many unanswered questions since the dramatic series of accidents, the local authorities launched an ambitious scientific program aimed at capturing, tagging, releasing and monitoring dozens of large bull and tiger sharks. But the study won’t produce any kind of results before several years. Impatient people were told to wait, as 300-kilo predators were captured and released in front of popular beaches. Yet, in the middle of 2012, most of the surfers were back in the water and 2011 seemed to be nothing more than a bad dream.

But reality stroke back and revealed the underestimated seriousness of the situation. At the family surf spot of Trois Bassins, dozens of people were enjoying the waves on the afternoon of Tuesday July 23rd. At four p.m., the surf schools called it a day and the students got out of the water. Half an hour later, Alexandre Rassiga, 23-year-old creole surfer, was bitten several times by a bull shark. He died of an hemorrhage at the hospital.

But reality stroke back and revealed the underestimated seriousness of the situation. At the family surf spot of Trois Bassins, dozens of people were enjoying the waves on the afternoon of Tuesday July 23rd. At four p.m., the surf schools called it a day and the students got out of the water. Half an hour later, Alexandre Rassiga, 23-year-old creole surfer, was bitten several times by a bull shark. He died of an hemorrhage at the hospital.

Two weeks later, it’s the world-famous Left of Saint-Leu that became the gruesome theater of a shark attack. This time, the surfer survived the accident but will have to learn to live without his right leg and hand. Even the most skeptical were confronted with the reality: Réunion Island faces the worst “shark risk” in the world. The problem could no longer be discarded as temporary. From then, it was considered dangerous to enter the water on most of the coast of the island, whatever the time of day, whatever the spot and water quality . The phrase “there are no more rules in Réunion” can be heard from the mouths of mourning and disheartened local surfers.

Some kind of routine slowly started to take place: after each accident, a protest breaks out, then a shark culling is organized, which in turn angers the various conservation NGOs and finally the internet is flooded with ever more hateful messages. The media was intrigued, and documentaries were broadcasted on well-known French TV stations and shows such as Thalassa and Envoyé Spécial. Discovery Channel releases a controversial “Shark Island” episode in its Shark Week series, with staged attacks and fake blood in the waves. The local surfers are shocked and infuriated.

From the first attacks in 2011, only surfers seem to be targeted by the large marine predators. The reasons are obvious. Since the spear fishermen were forced out of the water with the creation of the marine reserve, surfers are the only ones left where the waves break, usually on the back of the reef facing the open ocean. For this reason, responsible parents obviously forbade their children to keep practicing. People stopped taking classes in surf schools and spending their hard-earned money on expensive and now useless gear. “I didn’t make any money for 3 years. Zero,” says Mickey Rat, owner of a surf shop in Saint-Leu.

From the first attacks in 2011, only surfers seem to be targeted by the large marine predators. The reasons are obvious. Since the spear fishermen were forced out of the water with the creation of the marine reserve, surfers are the only ones left where the waves break, usually on the back of the reef facing the open ocean. For this reason, responsible parents obviously forbade their children to keep practicing. People stopped taking classes in surf schools and spending their hard-earned money on expensive and now useless gear. “I didn’t make any money for 3 years. Zero,” says Mickey Rat, owner of a surf shop in Saint-Leu.

Then, in July 2013, the “shark crisis” suddenly became everybody’s problem. During the holidays, a 15-year-old girl who was swimming just a few meters off the beach in Saint-Paul got attacked, and literally cut in half by a large shark. It’s the first accident involving a swimmer, meaning that it’s a “surfers’ only problem” no more. Sadness gives way to panic. The decision is made on July the 26th: until further notice, the ocean is forbidden from all marine activities on the open beaches of Réunion Island. Trespassers will obviously risk their lives, and could be fined for doing so. It’s a world first.

Luckily, two lagoons exist on the west coast of the island, and act as gigantic swimming pool cut of from the ocean by a barrier reef. Beach goers who wish to escape the tropical heat can enjoy the salt water of the Indian Ocean in security. But there are no waves to surf. The losses are substantial. Elsewhere in the world such as in California, Hawaii and Spain, economists calculated the value of a wave. It even has a name: “Surfonomics”. According to a 2008 study, the world-famous Mundaka wave in the Spanish Basque Country is said to bring between 1 and 4.5 million dollars annually to the local economy. All this money comes from the surfers who wish to try their luck on one of the best “sand bottom lefts” on the planet. On a global scale, analysts forecast the surfing industry to 13 billion dollars in 2017. No such study has been made on Réunion Island.

In just a few years, surfing in Réunion went from a noble and beautiful sport to a national disgrace. In schools, blond haired boys and girls are bullied for being “shark killers”. In social gatherings, one should avoid talking about their kids who enjoy sliding on water with a board. From now on, Réunion is known as the “Shark Island”, where surfers have become the destroyers of marine life, of the ocean, of the planet. “As surfers, we have always been environmentalists, says Patrick Flores, the coach of France’s surfing team. We work hard for the preservation of the ocean and the corals. For us, the reef is our life. We need it to stay healthy with an abundance of reef sharks. I’ve always said that in Réunion, we don’t have a shark crisis, we have a bull shark crisis. It’s very different. And now that I think about it, I don’t remember ever hearing the word bull shark before this whole story started.”

In just a few years, surfing in Réunion went from a noble and beautiful sport to a national disgrace. In schools, blond haired boys and girls are bullied for being “shark killers”. In social gatherings, one should avoid talking about their kids who enjoy sliding on water with a board. From now on, Réunion is known as the “Shark Island”, where surfers have become the destroyers of marine life, of the ocean, of the planet. “As surfers, we have always been environmentalists, says Patrick Flores, the coach of France’s surfing team. We work hard for the preservation of the ocean and the corals. For us, the reef is our life. We need it to stay healthy with an abundance of reef sharks. I’ve always said that in Réunion, we don’t have a shark crisis, we have a bull shark crisis. It’s very different. And now that I think about it, I don’t remember ever hearing the word bull shark before this whole story started.”

On this little volcanic rock in the middle of the Indian Ocean, this word is now on everyone’s lips. Yet, the Carcharhinus leucas is one of the least known and studied sharks even though this elusive predator has become a problem in France, Australia, Florida, Brazil and even all the way up the Amazon, some 3’700 kilometers from the closest shore.