The three lives of the Stavros amphorae

We sank beneath the surface, the green waters of late summer closed over our heads. We were diving the cove of Niolon, just southwest of Marseille. Fifteen metres into our dive, we spotted a cluster of elongated shapes buried in the sand beneath us, as we got closer the shapes took form – almost two hundred amphorae were lined up in the shape of the boat that once carried them.

This was the start of my investigation into underwater archaeology and the looting of wrecks in the land of cops and robbers… I had some pressing questions:

How is underwater archaeological research organised in France? Who owns the treasure discovered beneath the sea? What are the laws? Who are the looters? What is the going rate on the black market?

Questions that lead to more questions…

While the Department of Underwater Archaeological Research, part of the Ministry of Culture, believes in transparency, it does not infiltrate pirate networks and art traffickers with impunity.

Here is the story as I experienced it…

We glided above the wreck colonised by octopus, sea urchin and starfish beneath the sea grass that drifted back and forth with the swell of the sea, while Marine Jaouen, a research technician at the Department of Underwater Archaeological Research, filmed and processed samples in a cloud of bubbles.

This wreck was special. It had been completely rebuilt in November 2010 from a stock of Greco-Italian amphorae that dated back to the first centuries BC and were discovered just 50 years ago.

Marine Jaouen explained:

“We have an enormous amount of amphorae in storage that were discovered between 1952 and 1957 by Captain Cousteau’s team during the first archaeological digs he led on the Grand Congloue wrecks in the Riou Archipelago.

“Conservation was costing a fortune and transferring the amphorae to another storage location was financially prohibitive. The majority of the pottery remains were either broken or damaged. Museums were full and the remains, having been carefully studied already, had little scientific interest. Frankly – we didn’t know what to do with them!

“That was the basis on which this idea was born. We decided to re-submerge them, placing them, as they would have been found, in relatively shallow locations, for recreational divers to visit. The concept was to make an artificial reef that would give divers the thrill experienced by underwater explorers discovering a virgin archaeological site!”

And so it was that 200 amphorae were moved from Fort St Jean and submerged at the mouth of the Niolon cove, opposite the UCPA dive centre that keeps close guard on the site – the value of such treasures on the black market is high.

“The amphorae were secured in place with a steel cable to prevent looting. Cutting the cable would require heavy machinery and so any attempt to steal an amphora would guarantee it’s destruction,” said Marine. “Although I am under no illusions as to the corrosive power of the sea, we are more concerned with cruising boats, unaware of what is beneath them, dropping anchor on the site and destroying it. We dug deep though, through the carpet of sea grass and into the roots beneath the sand. Hard work under water – I can still remember it!” she added.

At the site, I framed an octopus in my viewfinder, it appeared never ending as it emerged from the neck of one of the amphora. Marine had asked me to shoot a series of photographs of the wildlife inhabiting the reef for the Marine Regional Park scientists who were studying the beneficial impact of the artificial reef with a view to supporting the argument for creating similar projects.

It was not a quick decision to put 200 artefacts back in the sea and there were lengthy administrative hurdles to overcome along the way. The first installation was established in the Debie cove in the Frioul Archipelago where almost a hundred amphorae were placed at a depth of 15 metres.

Richard Rech, president of Club Neptune, spearheaded the project; he put the file together and defended the plan, but it took all the pugnacity of the Department of Underwater Archaeological Research (in particular the director Michel L’Hour, the heritage curator, Patrick Grandjean and Marine Jaouen) to punch through the ministerial and administrative challenges and get green light for the project 18 months later. They were required to prove the environmental interests of the operation (neutrality of the pottery in a maritime environment and any impact on the sea life) and the economical interests (housing and security costs for the artefacts kept at the Vieux Port were considerable).

As I moved through the bed of amphorae beneath the green shaded waters of the Mediterranean in late summer, some of them dark, some cream, some scarlet, their elegant necks and handles beautifully crafted, I couldn’t help but think – so typical of the administration… these beautiful relics have spent the last 2000 years underwater, but still it must be proved that terracotta is harmless before putting them back!

At the Frioul site, I rotated an amphora, released by the storms, in the sand, over and over. Untouched by the passage of time, red, heavy, without a single blemish, it was as if it were fresh from Stavros’ pottery, his name newly engraved on the smooth neck.

Cristianini’s secret

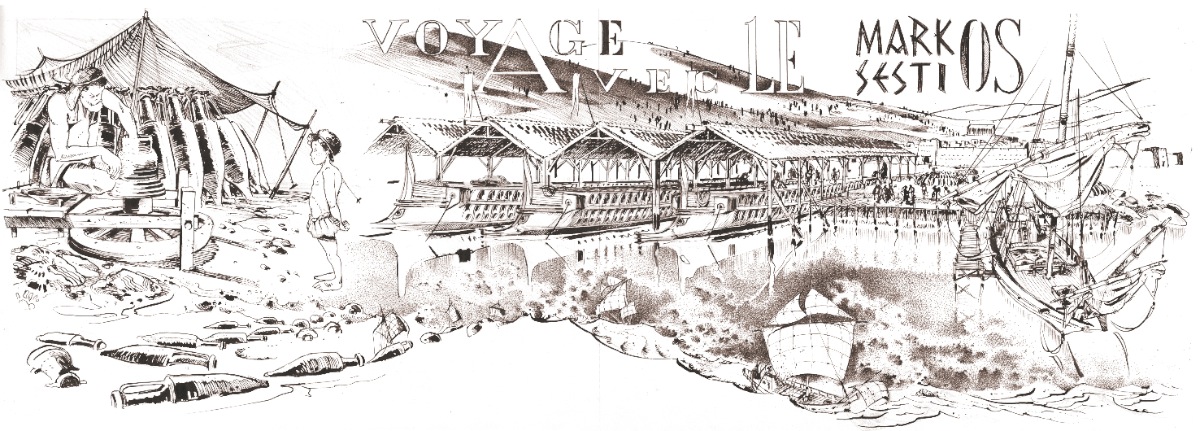

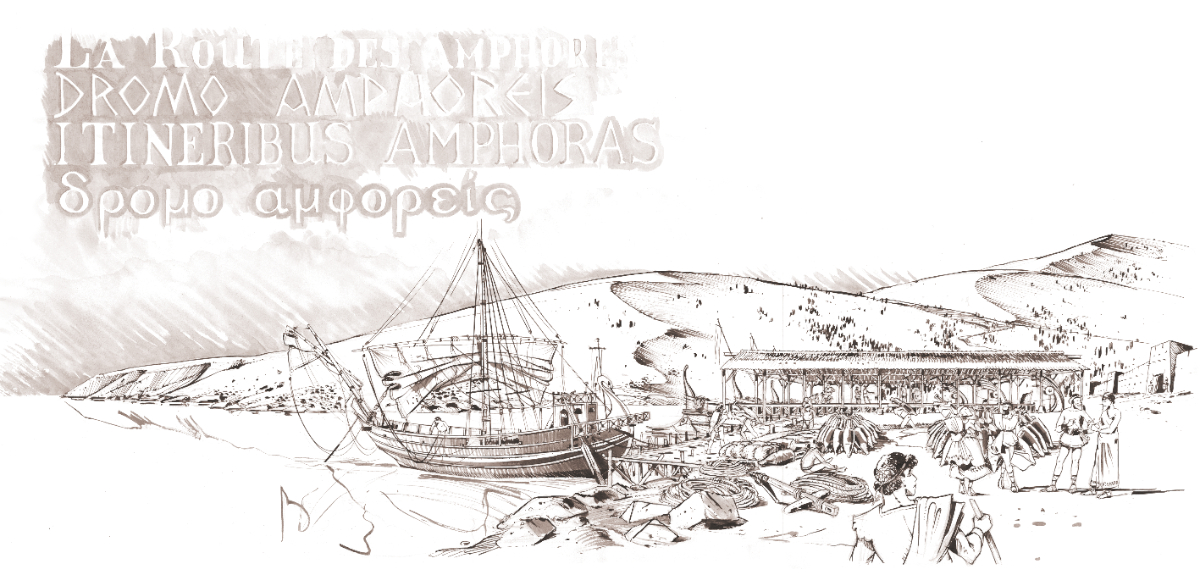

In Greece at the beginning of the second century BC, the Markos Sestios set sail for Marseille laden with 400 Greco-Italian wine amphorae, 7000 pieces of crockery and 30 or so Greek amphorae. The ship never made it. Perhaps knocked down in a gust of wind, it sank within miles of its destination at the Grand Congloue rock in the Riou Islands in front of today’s Marseille.

In the fifties, this was the hunting ground of Cristianini, a well-known local pirate. After suffering severe decompression sickness, he narrowly escaped total paralysis thanks to the nascent and pioneering Cousteau team who had one of the earliest decompression chambers.

In gratitude to Cousteau, Cristianini shared an extraordinary secret with him. While diving for lobster at the foot of the Grand Congloue, 42 metres down, he had stumbled upon mounds of “jugs”. An ancient wreck… Mountains of amphorae…

Jacques Cousteau immediately realised the importance of this site and from 1952 until 1957, led a campaign of discovery under the scientific direction of professor Fernand Benoit, director of antiquities in Provence. The dig was pioneering: for the first time ever a shipwreck was filmed using an underwater TV camera. This was the project that launched the Albert Falco, Captain Cousteau story – Falco was to become Cousteau’s right-hand and longest serving dive companion.

Hundreds of amphorae were raised; filled with air on the seabed and floated to the surface. Historic images; underwater archaeology was born!

But not without its fair share of uncertainty, errors and drama, as Luc Long, chief curator of heritage for the Department of Underwater Archaeological Research, described:

“The original explorers thought they were dealing with a single wreck. But thirty years later when their records were exhumed from the archives where they lay forgotten, the truth was revealed. All the evidence, doubts, sketches recorded in their notes pointed towards there being two ancient ships superimposed with two distinctly different cargos, both wrecked in the same place within a hundred years of each other. One wreck was hiding the other!”

And it was one of these very same “jugs” that I was rotating with fascination 15 metres beneath the surface. I laid it back down gently in the sand, infinitely aware that it had already had three lives:

The first when it emerged from the potter’s kiln, was carried by many hands from potter to dock to ship where it was filled with wine, and then shipwrecked and settled in a watery grave.

A second when the wreck was discovered and it was floated to the surface, studied and stored at the St Jean Fort where so many of its sisters had collapsed under their own weight.

And finally, a third and final resting place underwater at the Frioul Archipelago.

But it took only a brief sojourn on the surface with modern man to pique his interest. Collectors, speculation, piracy and trafficking… Born the same day and enemies by birth: piracy and underwater archaeology have circled one another since.

But this is not the end of the Grand Congloue story…

I had a rendezvous with Pierrot Vottero, a fisherman that hails from Port des Goudes in Marseille. It is said that fish is not his only catch of the day…